TESTIMONIES About Ramnicu Sarat

Rodica Coposu – When he got out of prison, he looked like a ghost.

“He went in prison weighting 112 kilograms and got out weighting 52, being 1.92 meters tall – I saw him three weeks after he got out of prison. He was wearing a shirt which was fluttering just like the shirts on the scare-crows in the fields of wheat, he was completely shaved on the head. I’m telling you something that has obsessed me for years and which I have told many times, but that I cannot forget – he was shaved on the head and you could see through the scalp the joints between the cranial bones, as we had learned at the anatomy classes in school. You could see them very well in his case, as you could see his teeth through the lips and he had very large edemas on his ribs and knees. He got out with hunger edemas of the IIIrd and IVth degrees; this is how the doctor diagnosed him, a prison fellow as well, who was under house arrest there.” (Interview with the Senior’s sister, appeared in Viata Buzaului[16], at the 10 year-commemoration of his death)

Here are some terrible testimonies about “the hell” at Ramnicu Sarat between 1947 and 1963 for those who still refuse to believe the truth about the communist prisons:

Ion Ovidiu Borcea “Ramnicu Sarat was the most tragic prison by means of its conditions, unique because of its harshness and duration. If Pitesti was characterized by collective violence, Ramnicu Sarat excelled through individual death in “the conditions” of the a la longue extermination, another devilish method invented by the K.G.B. tools.”

If it does not have the celebrity of Aiud, where I have also been until 1957, it is owed to the fact that the prison is infinitely smaller and had on its conscious a smaller number of detainees sent there to never return. It is not the same thing, dying in a cell with 4 or 5 other people around, and dying alone, after years of…torture. It was the road with no return, the prison without hope, from where we, the ones who left, were taken out by a miracle unforeseen by the communists. A torture or a pain can be shared and can be coped with more easily in a group than only by yourself, when you start to forget the day count, and you count the years according to the pass of the seasons. And if you add to that grave-like-silence in the 36-cell and 36-detainee prison, where not even the guards had chairs to watch day and night, the hunger, the cold, the isolations, the loneliness, the count of the dead, the lack of information, the unknown of the following day, the sinister silence and the lack of hope, you are left with the only “success” that you did not hook it before your fellow, your best friend did.

Nicolae Steinhardt in “The Happiness Diary” describes a scene that he witnessed: “He comes from Ramnicu Sarat, where he lived six years (five to be more exact), alone in the cell, subject to a starvation diet, he ate the straws in the mattress (torn) on which he slept, eventually all of them, only the sack cloth was left. Ion Mihalache died in the nearby cell after he had gone blind.” “This MAN, who was an example of behaviour, did not die of natural death. He was deliberately assassinated because he would continue to remain a symbol of the Romanian resistance. He protested countless times, making the whole penitentiary sound. The political officer and commander Visanescu would permanently beat him, they created conditions for him to get sick and did not give him medical assistance. They would enter and throw water on him with the bucket in the middle of the winter. I watched his cell through the six holes that I had made in the door with a wire. They would beat Ion MIHALACHE every day until he died. If I hadn’t been there, this testimony would not exist. Now that I am a free man, I have the duty to announce this assassinate committed by commander Visanescu. The cries: “Brothers, this is Ion Mihalache. They are killing me!” sounded daily in the penitentiary. This murder cannot be forgotten”.

Augustin Visa is telling: “I was taken to the first floor, in a small cell, with a bed, a three legged table, a small bench, a vessel with water and the tub... The door was of massive iron, with a visor and an opening for the food mess kettle. A small window with the shape of a crenel brought in the tiny room an opaque light. I see that the ceiling is made of thick, corrugated iron over which there was brick covered with asphalt, so was the floor…they took off the cuffs on my feet. They had tried to cut the rivets for two days. The chisel was blunted and the anvil was moving under the hammer blows. They didn’t have a jigsaw. I had awful pains… There was silence everywhere as if in a cemetery. The guards had felt shoes so that we couldn’t feel them, so that they could supervise the interior of the cells without being heard”.

Ion Diaconescu: “The isolation measures, that not even the Security used, overcame any imagination, the detainee was not supposed to see any other human being, but for the guard on duty who was in the morning shift, without saying a single word. Those who served us food were orderly duties but, in five years and a half, the time I spent there, I did not get a glimpse of any of them, not only once… Nobody would enter our cells alone, they would always be accompanied at least by the guard on duty, so that the possibility of any discussion between people could not appear… They had created a perfect draconic system to destroy all our spiritual springs. That is, the ones who had survived the periods of starvation and torture extermination were going to be psychically destroyed by means of these unseen measures of isolation…But wickedness had no limits, on the contrary, the more important a detainee was considered, the harsher the treatment was, meaning that he was considered a dangerous enemy of the regime and had to be eliminated somehow!...”

Victor Anca summarises the Ramnicu Sarat experiment: “The conditions at Ramnicu Sarat were of a savagery that the mind of a sane person cannot believe that were possible. This was the product of the animal-man, made by the totalitarian regime. Reading nowadays the literature about the extermination camps in the Marxist USSR and Hitlerist Germany, we, who have survived Ramnicu Sarat, see that communist Romania under Gheorghiu-Dej wasn’t below in any way and it had its Beria, Dzerjinschi, Himmler, Eichman or other horrid criminals – ours were called Alexandru Vişinescu, Alexandru Nicolschi, Pantiuşa Bodnarenco or other names as sinister as these ones. (in Ion Diaconescu, Cicerone Ioniţiu, Prin ungherele iadului comunist-Râmnicu Sărat[17], Bucharest, 2007)

Moral Romania

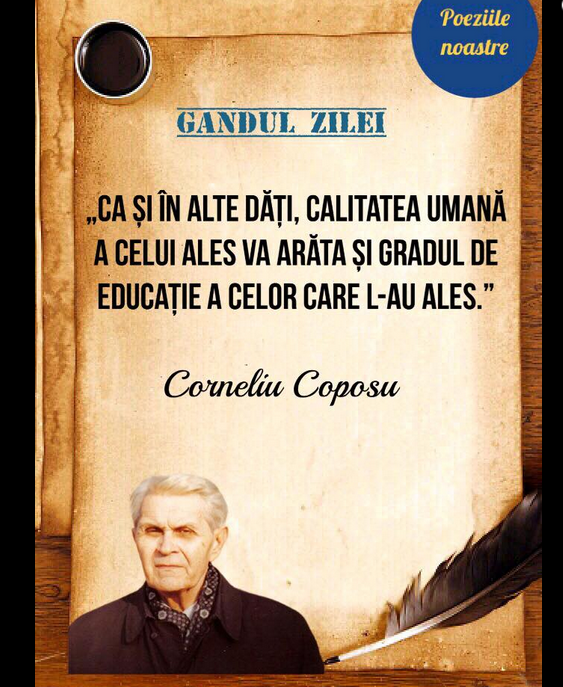

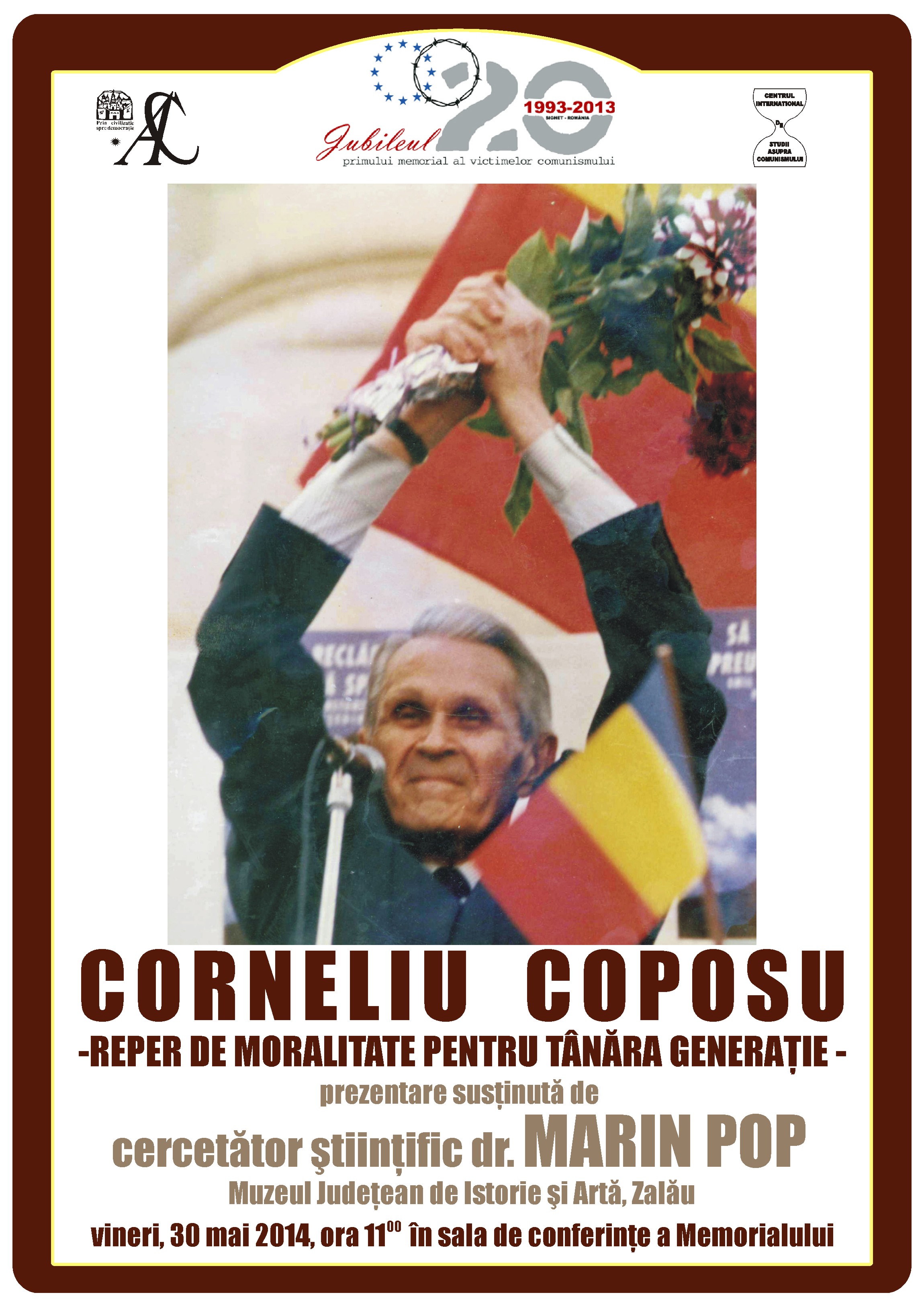

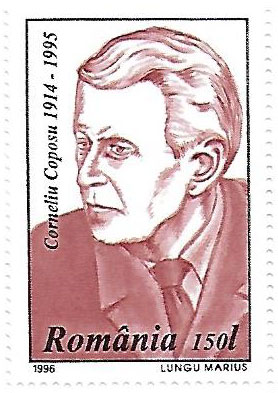

Corneliu Coposu was one of the brightest personalities of moral Romania. Unforgiving at 20, patient at 30, serene at 80.

“You were not a state president, or a minister, or an army commander, or an academician and not even an ambassador. But you did not need these titles to make your name well-established and respected everywhere”, the ambassador of France in Romania, Bernard Boyer, said at the awarding of the National Order of the Legion of Honour of the French Republic. Complex through his simplicity, great through his modesty, majestic through his intransigence and unabdication from his principles. He wanted only one dignity, that of a man of character, that of a Man with capital M. In a nutshell, one of those men of the nation who loved their country and believed in its historical destiny. The foreign analysts noticed his personality more exactly and reproduced it more graphically. Maybe because they understood that “such people are born at every half of a millennium.” According to Lech Wallesa and Soljenitin the Era of the political experiments passed and along with it the era of the great heroes of history.

The political guinea pig in the Ramnicu Sarat prison will be a Tribune of contemporary Romania in a country destroyed by vanities and ambitions for Power.

“A giant among people” David Funderburk, a former ambassador of the USA in Romania, said at his death, “a genuine champion in the fight for liberty and democracy”. The same person concluded “he was a patriot, in the real sense of the word, Romania lost one of its greatest values and a political character of maximum integrity.” The political guinea pig from the Ramnicu Sarat prison defeated the torturers and followed his destiny like the great Tribunes of the nation.

*

Corneliu Coposu proved his verticality under all circumstances. Especially as a winner. He spoke about his torturers without hate and wish for vengeance. “I don’t hate them, but I don’t understand them either!” Corneliu Coposu said harshly. (P. 188, In fata) But he kept an endless pain towards the colleagues of suffering, towards the millions of innocent people thrown after bars. “A piece from my soul remained there, near the friends that died, a part from my life is still there… Maybe a piece from the history of this nation…” (p. 187, In fata)

He died the same way he lived, on the barricades of the ideals, on duty. He did not spare himself until the last moment. His sister, Mrs. Rodica Coposu, was wondering rhetorically, at the ten-year commemoration of his death, “why he did not protect himself at all, considering that he was ill”. The answer came naturally. “He did not want any kinds of dignities. He had a creed which he followed and gave his life for this creed.”

“Everything is about the survival of an attitude. If it triumphs, my disappearance is no longer important”, the Senior confessed shortly before the Great passing away.

From the Pitesti Phenomenon

Out of the properties of the most used methods of oppression used by the Security, violence was on the first place. The crowbar beating was for a long time the most frequent method of moral humiliation of the political prisoner. Besides the inquiry when the detainees would be naked, the crowbar represented the extreme phase of violence. Petre Tutea remembers shiveringly: “The hands and ankles are tied together, a crowbar is placed under the knee joints and is sustained at its ends so that the victim hangs with the head downwards and is beaten with a stick or a metal rod at the bottom or at the soles.” (Intre Dumnezeu si neamul meu[18], Bucharest, Anastasia Publishing House, 1990, p. 346). By far the most draconic, primitive and punitive system of detention was the one at the Pitesti penitentiary. Starting with 1949, at Pitesti was carried out the most inhuman process of re-education and extermination, an unprecedented experiment in the oppression annals. Just like at the gates of hell, the detainees were encouraged to leave behind all hopes. “There is neither mercy, nor sympathy for the enemies of the people” had been written on the frontispiece of the prison. The raw material of the hallucinatory experiment were the students, the most refractory and non-conformist social class who, if at large, could have started a riot or popular protests at any time.

The Pitesti experiment is a genuine Romanian creation, having as a leitmotif the reeducation. The scenario, (see Costin Merisca, Tragedia Pitesti[19], The European Institute, 1997) was minutely elaborated even since the summer of 1948 when it was decided that Pitesti should become a prison of penalty execution for students. Eugen Turcanu together with other colleagues, members of the Organisation of the students with communist convictions applied a devilish plan of reeducation by means of torture. An organized violence that did not miss complete isolation, beatings of the detainees that they would strip naked, but what was more inhumane, the compulsion to cooperate against your own friends and colleagues. At least in the fist part “…torture is the key of success. Along all these phases, confessions were almost regularly interrupted by torture”, but torture was not just a simple beating. “…During the reeducation you would share the cell with the investigator who would not give you a moment of rest. You could sleep at night, that is correct, but only on your back, completely naked, with your hands stretched over the blanked. And if you moved while sleeping or tried to turn on one side, you would be hit in the head with a club by the reeducator on duty.” (Virgil Ierunca, Fenomenul Pitesti[20], Humanitas Publishing House, 1990, p. 36). Therefore, a permanent terror, by day and night, to determine “the breaking of the past”.

The Pitesti phenomenon would have several stages. The external exposure, the internal exposure and the public moral exposure. (V. Ierunca, Fenomenul Pitesti[21], Humanitas Publishing House, 1990, p. 33-34). Self-exposure was the preliminary stage of the proper reeducation, a sort of brainwashing before receiving the Marxist-Leninist teaching. Like in the entire communist mythology, a complete and profound reeducation was hoped for, going to the most intimate springs, but with the most barbaric and primitive methods. The fist stage was the external exposure, divulging the deeds undeclared at the Safety, so that the internal exposure would be made in smaller collectives. “After the external exposure, that is divulging the deeds undeclared at the Safety, it would follow, in smaller collectives, a new stage, the internal exposure. While remembering, they would write with a pin on the soap, chronologically, all the inimical activities that they had attended, starting with their arrest, but also all the thoughts hostile for the regime that they had had in that period of almost two years, a so-called moral exposure. When somebody considered that the person is relatively ready, they would announce the room collective that would prepare the person for the verbal confession, in everybody’s hear.“ (Costin Merisca, Taramul Gheenei[22], p. 123, Porto Franco Publishing House, 1993).

There was another type, the public moral exposure. “The detainee has to trample everything that is sacred for him, and, first of all, his family, God – if he is a religious person, his wife or girlfriend, his friends, himself. Each person’s past is analysed step by step, on his ground the most monstrous version has to be invented. His father, for example, has to look like a crook, a bandit, a bribe taker. Since among the detainees there were many boys from the country – and therefore some of them were sons of priests - , the latter are obliges to describe in detail the erotic scenes to which their fathers had taken part right in the altar while preparing the Eucharist bread. And the mother was presented like a prostitute, the detainee was obliged to invent, as detailed as possible, the scenes which he himself was supposed to have attended. About himself, the detainee finally had to imagine the most refined perversities. Nobody gets away without covering with mud, in public, the living springs of his life, until the last bit of his past, that he could hang on afterwards to remake his personality, hasn’t disappeared.” (Virgil Ierunca, op. cit., pag. 33-34).

The most ferocious stage of this kind of reeducation, torturing indeed, was invented, as well as the entire proceeding, by Eugen Turcanu and his group. In the properties of this proceeding, beating was in the foreground. The detainees would go through a purgatory of terror and humiliation. The violent beating, in group, considered the most ferocious method, with a bewildering impact, followed by a psychic torture, 24 hours out of 24. In any second, day or night, the nightmare would start again after a hallucinatory scenario of the unleashed horde who would innovate every time as far as terror was concerned. The torturers would follow an exact scenario of beating, regulated in detail, but with freedom of creation as far as terror was concerned. The detainee was brought to the last stage, the stage of extreme uncertainty with the final solution – the complete abandon in the torturers’ hands.

Sighet – the Penitentiary of the Romanian Elite

“Sighet” exceeds any other communist penitentiary through the rapidity and efficiency of extermination. If “Pitesti” appeared in 1949, a year after the complete dissolving of the democratic institutions, Sighet marks a peak in the communist oppression. Between 1950-1955 this was the place where the great figures on the interwar period found their end, starting from Iuliu Maniu to ministers, generals, academicians, bishops. Hunger, isolation and beating were the constancies of a detention system whose purpose, either hidden or expressed, was the physical elimination of the cultural, economic and political Romanian elite. “The prison in Sighetul Marmatiei was chosen for the great dignitaries of the country taking into account several strategic reasons. They would try to take the elite people as far as possible from Bucharest, as far as possible from the great centers of the country, to a place as isolated as possible. Sighetul Marmatiei corresponded these criteria as it is plunged into the Maramures Depression and at the border of the country. But not any border, but right near the border with the former Soviet Union. The prison here corresponded the most the extermination plan that the communist regime had for the great Romanian dignitaries, because, should anything happen against this regime, they could have been crossed the border in the Soviet Union easily and fast. The Soviet railway line with broad rail gauge passed through Sighet, thus ensuring the embarkation and deportation directly in the Siberian wilderness.” (Nutu Rosca, Regimul de izolare, in Memoria inchisorii Sighet[23], The Civic Academy Foundation, 1999, p. 144).

Among the constancies of the detention system at Sighet it is included the very strict interdiction to communicate with the exterior. “During this entire period, the more than two hundred prisoners were not allowed or able to send any letters from here. For five years and six months, the detainees couldn’t and didn’t send a word outside the walls of the prison.” (Ibidem, p. 145). It is written about one of the most select detainees, the former minister of external affairs and economist, Mihail Manoilescu: “Keeping him in detention in the Sighetul Mamatiei prison, as well as the other dignitaries, was so secter that not even the tribunal, that was going to sentence him, did not know where he was.” (Ibidem, p. 146). The only possible communication with the exterior would be made only through the General Direction of Penitentiaries in Bucharest and only concerning the death of the detainees, by means of a simple code. “Lightbulb number 2 was put out” was transmitted to Bucharest when Iuliu Maniu died.

In the first lot, on the 5th of May 1950, 84 former ministers, subsecretaries of state, governors of the National Bank of Romania and former governors of Basarabia and Bucovina were arrested and imprisoned.

What was the objective in the Sighet prison? According to Decree no. 6 on the 14th of January 1950, on the basis of which the labour colonies (camps) were founded, in the foreground there was “the reeducation of the inimical elements in the Romanian People’s Republic also in order to prepare and place them in the social life, in the conditions of the popular democracy and of the development of socialism.” But reeducation was only a pretext, part of the detention programme, the hidden objective being the extermination itself. Unlike Ramnicu Sarat, at Sighet they would read and comment upon newspaper articles, in groups of course, under the strict monitoring of the supervisors who would periodically make reports concerning the political prisoners’ mood. (Ibidem, p. 212)

The life of the 70 priests and high Catholic prelates imprisoned at Sighet was identical with the slaves’ life, as cardinal Iuliu Hossu confesses, but it would allow certain loosenesses, unimaginable for the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary. (Ibidem, p. 138). “Afetr we met each other 150 – we were in a select society – , we made a daily programme. We woke up at 5 o’clock in the morning and went to bed at 10 o’clock in the evening. We organized our day time so that we prayed, meditate and performed the Holy Mass (only the recited prayers) together. At times, a bishop would hold a conference. The conferences held by His Excellency Marton Aron about his predecessor, Bishop Mailat, were very interesting. His Excellency Pacha would tell us his “vices”, that is funny stories which he would tell with exquisite art and fine sense of humour.” This was a day at Sighet, totally different despite the humiliations of the kind presented by priest Alexandru Ratiu (Ibidem, pag. 129-131): “…we, the priests, were the porters of the prison. When they would receive provisions, maize, pearl barley, beans, we were obliged to carry the sacks up, at section number 3, where there was a warehouse. They would oblige me, the youngest, and Father Danila Berinde to carry on our backs 90-kilo sacks. We had 51 stairs to climb. When we reached the top, the heart would beat angrily in the chest.” The same testimony appreciates in conclusion: “…the conditions at Sighet were terrible, for most of the elders, and shook all detainees’ health. And when we got out of prison, we found our lives destroyed” (Ibidem, pag. 132)

In the Detention System at Ramnicu Sarat

The political detention system in the Romania of the 50’s has a few constancies: beating, hunger and isolation. Although the three punitive measures were used in all penitentiaries indiscriminately, the methods of putting them into practice varied from one prison to another.

“At Aiud I saw people that had gone crazy because of hunger”, said Constantin Cesianu in a confession appeared in Arhivele totalitarismului[24] (The 5th year, 1993, no. 1, pg. 116). The case of Dr. Dumitrescu from Buzau is given as an example who died begging “I want milk, I want milk!”. In the Aiud penitentiary the political prisoners had only one wish – “In our sleep, we would all dream that we were eating”. Despite that, there was a penalty much more difficult to bear. Here is an indeed terrible confession. “I thought and asserted that hunger is man’s greatest enemy. Today, I say, though, that above hunger lies loneliness” Ibidem, pg. 112, Nae Tudorica testimony).

This hierarchy of the punitive measures isalso confirmed by the testimony of the Greek-Catholic cardinal Alexandru Todea, sentenced to life imprisonment by a Military Tribunal in Bucharest in 1950. On the 2nd of March 1952, Alexandru Todea was transferred to the Sighet prison together with other 12 bishops and Greek-Catholic and Roman-Catholic priests. “After a few months, in 1952, a political officer came and informed us that we had been proposed to work in prison, I had been appointed the chief of this work group, because I was younger and more vigorous than others (…) We have always worked energetically because we knew that our work was useful to all the detainees and, especially to the lonely ones, isolated in their cells, where existence was mistaken for suffering, isolation for all the misery of the communist prison”. Isolation was therefore the harshest way of punishment at Sighet too, only that the Catholic and Greek-Catholic prelates managed to break the wall of silence and give them the blessiong of communication and Eucharist. As in the communist prison any way of communication, be it in the plainest shape, automatically meant Eucharist, a blessing of the Divine even when it was not invocated. “This is how I found out, Alexandru Todea continued his confession, where George Bratianu was, as well as Iuliu Maniu and other generals. Among them, general Ilcus, who had lost the sense of reality, in other words, he had gone mad. I found out later that he had been a very decent soldier, but the isolation for more years, as well as the suffering had brought him in the state that he was. Yet, he benefited of a great favour because the Greek-Catholic bishop Ioan Ploscariu, incarcerated too, was placed in his cell to help him. He would calm him down in the moments when he was clamouring and managed to convinge him to end his manifestations because the Militia officers were mocking him.” (Memoria[25], 1993, no. 27, pg. 121).

The Isolation

Isolation was the watchword of all the political prisons in Romania, but the extent of success was different. The only way of succeeding was the black one, where, besides quasi-total isolation, the detainee was punished with the reduction of the food portion.

At Ramnicu Sarat, along with the isolation from the exterior, suitable for all the Romanian political penitentiaries, the Isolation from human beings, with capital I, was of daily usage. Here are some comparative excerpts, Aiud – Ramnicu Sarat, at a distance of a few months, belonging to Ion Diaconescu (cf. Temnita, Destinul generatiei noastre[26], Nemira Publishing House, Bucharest, 1999). “I was, therefore, isolated, but this didn’t impress me in any way. I knew from my own experience that the isolation from Aiud, by means of objective compelling, couldn’t be as strict as the one from the Security”. And the foresights of the young political detainee became true. “Barely placed in the new cell, I made contact with those around me, either by means of knocking in the wall, or yelling at the window and from them further on, just like heat through conductivity, I colligated with most of the lodgers in the cell (…) and from these friends started to arrive the second day, through the reliable officers on duty or the imprisoned doctor, who had the freedom to move, all sorts of messages written on cloths with ink made from soot or by means of other systems which reminded me of the first period, in the years of 1949-1950, also spent in cell” (Ion Diaconescu, op. cit., pg. 218) Messages would circulate pretty vividly, conversations, even if only at a shutter, would lead to the establishment or the re-establishment of new friendships, of fragile but hope and strength of resistance giving inter-human relations. Moreover, this freedom of communication had an immediate and convincing impact on the morale. “…My relations in this period (of isolation – n.a.) with the colleagues in the prison were limited only to written or oral messages, sent via the officers on duty or the doctor, as well as knocks in the wall. Yet, I befriended by these means with some people that I have never actually seen in my life” (Ibidem, pg. 222).

Let us see how the same Ion Diaconescu perceives the same phenomenon of isolation one year later, this time in the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary. Which are his relations with his fellows, with the colleagues of suffering?

“The methods of isolation, unseen not even at the Security, exceeded all imagination. According to the measures taken, the detainee didn’t have to see any human being, besides the guard on duty who would do his morning tour without saying a word”. (Ibidem, p. 234). Each detainee had to obey the daily programme and the Interior Regulation: “after waking up at 5 a.m. – n.a.), the detainees had to make their beds following a precisely indicated technology and from that moment on, until 10 o’clock in the evening, you were strictly forbidden to touch it! Meanwhile you were allowed to walk quietly in the cell or to sit on the little chair, with your face towards the visor, so that the guards could see you at any moment. While sitting on the chair, you couldn’t sleep, and if you were caught with this major guilt on you, you would be punished. Also, you were not allowed to make noise in the cell, which could have been heard by the neighbours, you were not allowed to climb on the window and you were not allowed to knock or even touch the walls in order to try to make a connection with the other detainees.” Moreover, after each meal “the mess kettle and the spoon were taken out of the cell so that we could not keep any metallic objects, and generally, no objects at all, except those with which the cell was equipped.” (Ibidem, pg. 234). In order to make safety measures more strict, “nobody entered our cells alone, but always accompanied at least by the guard on duty, so as not to create the possibility of any discussions between people.” Ramnicu Sarat seemed a non-violent alternative, but it was not below the Pitesti phenomenon in any way. Instead of the hunger and the beatings, at Ramnicu Sarat the extreme, total isolation was introduced, a method of brainwashing which would have allowed at any moment the conversion to other values. The most capable political prisoners managed to break the wall of isolation, the classic language was replaced by Morse signs, coughed Morse or even the language of the doors. Luck only helps the audacious. “Only this way did we manage to break the wall of this fantastic isolation and thus manifest ourselves like human beings. Because how could you call human beings those who would stay locked in some cages for five years and a half, without being able to know anything of what is going on around them, without seeing anybody or talking to somebody” (pg. 251).

STALIN’S CODE

After the revolution in Hungary, at the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary the rules of the cage, of the total and permanent isolation, were experienced for the first time. Another penitentiary code of conduct, based on illogical, absurd and inhumane rules. The norms of a code equally absurd and inhumane were created on this basis. It is probably one of the harshest codes of penitentiary conduct invented by the human mind. A French moralist, Girard, wrote that at the basis of any Regulation, of any code of human cohabitation must stay two principles, ethics and mercy or charitableness. Any deviation from these principle s turns even the most honorable through its intentions regulation into an obsolescent one. Besides, the notion of rule comes from the Latin word regula, which literally represents the tool with which one draws a straight line. In The Spirit of the Laws Montesquieu considers that “the law is, in general, the human reason as long as it governs all the peoples of the world”. On their turn, other philosophers concluded that rules must be based exclusively on reason, as long as the laws of hazard are based on whims and errors. The penitentiary universe at Ramnicu Sarat stands on another Code of conduct which proclaims the inhumane, breaks and forces the elementary rules of the logic, even logic in general. Absurd and illogical rules, imposed by means of force, starting from the fist day of detention until the last one.

Non-Violent Terror

Theoretically, at the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary beating was only rarely used. This method was probably part of the same devilish system of thinking, any act of correction being the equivalent of a human gesture, of an indirect recognition of the detainee’s existence as a physical person. Or, it was normal, according to this bizarre logic, for the detainee to want to be beaten just to feel that he exists and that he is not completely ignored as a human being! The simple penalties were reduced to isolation, actually to the removal of the bed from the cell so that the detainee does not have a place to sleep, or of the straw mattress, as well as the reduction of the daily portion of food. The regime of extermination, the total and permanent isolation, guards wearing felt shoes who would watch the detainee through the visor and would punish him for the slightest breaking of the regulation. A regulation, with capital R, equally absurd and inhumane. The first contact of the political prisoner with the prison consisted of learning this internal Regulation. The rules were simple and easy to remember. The monocell conditions, with one political prisoner in each cell, made the application of the internal rules simpler. The daily programme was well delimited. Getting up at 5 o’clock in the morning and going to bed at 10 o’clock in the evening. Here is how Ion Diaconescu describes the rules at Ramnicu Sarat: “After waking up, the detainees had to make their beds following a precisely indicated technology and from that moment on, until 10 o’clock in the evening, it was strictly prohibited for you to touch it”. Other confessions and declarations demonstrated the drama abode by the political prisoners who would break this interdiction.

When 64 years old, counter Admiral Horia Macellariu addressed in a memorial to the management of the General Direction of Penitentiaries. “In this health and age condition, I am obliged to comply with hardened execution conditions because of which I am not allowed, if needed, to lie down daily for 17 hours and the diet – which I had at the Aiud penitentiary because of my disease – is suppressed.” Most of them ill, old, in pain and, moreover, hungry, the political prisoners were forced to sit on the little chair for 17 hours facing the visor. Any breaking of these rules would cause further penalty days, most of the times of isolation again. Another rule stated the interdiction of falling asleep on the small chair. Other days of penalty for simply dozing off.

The obligation to sit fixedly on the chair, otherwise the only activity allowed in the cell, was followed by numerous interdictions: “You were not allowed to make noise in the cell, which could have been heard by the neighbours, you were not allowed to climb on the window and you were not allowed to knock or even touch the walls in order to try to make a connection with the other detainees” (Ion Diaconescu). Other restrictions concerned the plates and dishes:”…after eating, the mess kettle and the spoon were taken out of the cell so that we could not keep any metallic objects, and generally, no objects at all, except those with which the cell was equipped.” The measure was taken so that the detainees would not try to commit suicide or use the tools to communicate with the others.

A Quasi-Perfect Gulag

Alexandru Draghici, the minister of internal affairs and his countryman, Alexandru Visinescu, perfected a system of an unusual harshness in which beating was used more rarely, but more drastically and more punitively, the so-called group beating. Just like at Pitesti, group beating would increase the intensity of correction and the strikes could not be counted or individualized. The same Alexandru Draghici had forbidden beating in 1953 by means of a written directive!

The few survivors gave their opinions about the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary but an exact characterization will probably be made by a neutral but very well informed character, far from being suspected of any partisanship, Ion Mihai Pacepa. The former chief of the Security, speaking about Vasile Luca, whose file he had worked on (Cartea neagra a securitatii[27], pg. 193-194), concludes harshly: “At the end of the trial, vasile Luca was sentenced to death. Gheorghiu-Dej, “large-hearted”, commuted his sentence into hard labour for life but took care that Luca was sent to the extermination prison in Ramnicu Sarat where he was kept in total isolation until his death”. Therefore, in the 50’s, the destructive character of the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary was notorious. Let us add that at least in certain periods, the former communist minister of Finance, Vasile Luca, benefited of numerous privileges!

About Isolation and Loneliness one can speak on close terms, the two experiences having similar points here and there. Fosco Maraini describes in the volume The Hidden Tibet the phenomenon “of death in solitude”. “Solitude is such a powerful experience that leaves inerasable traces on the person who lived it; the chosen ones complete the flame of their spirit, but for common people the same flame diminishes or is put out. Like the poisons which, in certain quantities and on some bodies, have a miraculous effect, and in other cases they are deadly. Who hasn’t heard of the dead in solitude?” About the dead in solitude at Ramnicu Sarat will also speak Corneliu Coposu.

At Ramnicu sarat, brainwashing was made indirectly. There was not a third way between reeducation and suicide. Constantin Titel Petrescu, the leader of the Romanian Social-Democratic Party, philosopher Ioan Petrovici abjured in order to get out from the hell at Ramnicu Sarat. The powerful ones, like Ion Mihalache, refused any collaboration, did not deny their convictions. Neither Nicolski, nor patriarch Justinian Marina managed to determine Ion Mihalache to betray his ideal. The miracle of survival was bound to strong characters, to the chance on Morse communication but also to hazard. The others died or ended their lives. At least three detainees committed suicide in the prison at Ramnicu Sarat – Dinu Neagu, Jenica Arnautu and Nicu Adamescu. Teacher Dinu Neagu from Macrina village near Ramncu Sarat was arrested, beaten and imprisoned several times between 1947 and 1959. In September 1959, while incarcerated at Ramnicu Sarat, he is said to have hung himself with the bed-sheet of the cell bars. This is the official version. The Neagu case was widely discussed in the post-December media, but an eye-witness, guard Panturu, admitted in 1990 that the former teacher from Macrina died consequently to the beatings received in prison with the help of the Security.

Jenica Arnautu was sentenced to hard labour for life, being incarcerated at Ramnicu Sarat. He died on the 2nd of November 1959, after a prolonged hunger strike. It is said that his gesture wanted to be a general protest against the conditions of detention in the unusual prison.

The Ramnicu Sarat experiment, as it was such a thing, appeared after the failure of the Pitesti phenomenon, whose negative echo crossed over the borders of the country. Ramnicu Sarat is also a Romanian creation from another period, of a relative calm and social peace, of a relative thaw on the international relations. The adhesion of Romania to the United Nations Organization and the Geneva Convention in 1955 imposed a new conduct, on the other hand the revolution in Hungary drew attention on the fact that on an internal plan numerous factors of risk had survived., Beating was going to be, at least theoretically, removed, out of the arsenal of punitive methods, but at the same time, the class enemy had to be eliminated. This is how the Ramnicu Sarat appeared, a version which was not below the Pitesti Phenomenon in any way.

The coordinates of this historical epoch are the number-individual, the penitentiary of total isolation and the totalitarian communist regime. Three complementary systems, having as a common point the Terror. Historian Denis deletant draws the attention that minimizing or underestimating such moments and historical characters do not comply with the historical truth:” Initially, Romania, like all the communist regimes in East-Europe, was based exclusively on the use of terror as a tool of the political power. This terror unfolded in two phases, in the first phase the adversaries of power consolidation were eliminated, and in the second phase there were applied methods to ensure obedience, since the revolutionary change had been accomplished”. (Teroarea comunista in Romania; Gheorghiu Dej si statul politienesc[28], 1948-1965, Polirom Publishing House, 2001, pg. 10)

A key-event in imposing terror as a method and tool of political domination took place immediately after the Soviet troupes entered the country. On the 24th of March, a few days after the installation, the new Petru Groza cabinet moved the Special Information Service from the Ministry of War in the direct subordination of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers , the first step towards the political police (see Cu unanimitate de voturi. Sentinte publice adunate si comentate[29] by Marius Lupu, Cornel Nicoara and Gheorghe Onisoru, the Sighet Library, 1997, pg. 9 and the following). Between 1947 and 1948 several waves of arrests took place, the “reactionary-fascist” currents being, on the one hand, “the iron guards” and “the Hitlerists”, and on the other hand the historical parties, the NPP, the NLP and the SDP – Titel Petrescu. Setting up the General Direction of State Security, in August 1948, marked a new stage of the class enemy elimination. Tens of thousands of people will be investigated by the Security and will go to political prisons. Stalin’s death did not change the data of the problem in Romania, on the contrary. Nicolae Steinhardt appreciated the Romanian phenomenon at its real dimension: “The political arrests during 1947-1950 may have had a character of political terror. The ones between 1958 and 1959 were only demented. The regime was strengthened, all political justification is gone.”

In March 1957, the Security personnel were increased. 2.059 officers and 429 soldiers were added to the 13.155 militaries and 5.649 civilians. The wave of terror set up after the retreat of the Soviet armies from Romania led to new waves of arrests, more than 6.362 detainees in 1958 alone. Among the victims were two groups of writers and scholars foremost of whom philosopher Constantin Noica, Nicolae Steinhardt, Alexandru Paleologu, Alexandru “Pastorel” teodoreanu or Constantin Pillat. The new period of terror will climax with the interment in the labour camps of more than 40.000 people. The most feared adversaries of the regime will be sent to the prison of extermination at Ramnicu Sarat.

[16] Viata Buzaului (approx. The Life of Buzau)

[17] Ion Diaconescu, Cicerone Ioniţiu, Prin ungherele iadului comunist-Râmnicu Sărat (approx. Ion Diaconescu, Cicerone Ioniţiu,in the Corners of the Communist Hell – Ramnicu Sarat)

[18] Intre Dumnezeu si neamul meu (approx. Between God And My People)

[19] Tragedia Pitesti (approx. The Pitesti Tragedy)

[20] Fenomenul Pitesti (approx. The Pitesti Phenomenon)

[21] Fenomenul Pitesti (approx. The Pitesti Phenomenon)

[22] Taramul Gheenei (approx. The Realm of Gheena)

[23] Regimul de izolare, in Memoria inchisorii Sighet (approx. The Isolation Regime in The Memory of the Sighet Prison)

[24] Arhivele totalitarismului (approx. The Archives of Totalitarianism)

[25] Memoria (approx. The Memory)

[26] Temnita, Destinul generatiei noastre (approx. The Dungeon, The Destiny of Our Generation)

[27] Cartea neagra a securitatii (approx. The Black Book of Security)

[28] Teroarea comunista in Romania; Gheorghiu Dej si statul politienesc (approx. The Communist Terror in Romania; Gheorghiu Dej and the State Police

[29] Cu unanimitate de voturi. Sentinte publice adunate si commentate (approx. With Vote Unanimity. Gathered And Commented Public Sentences)