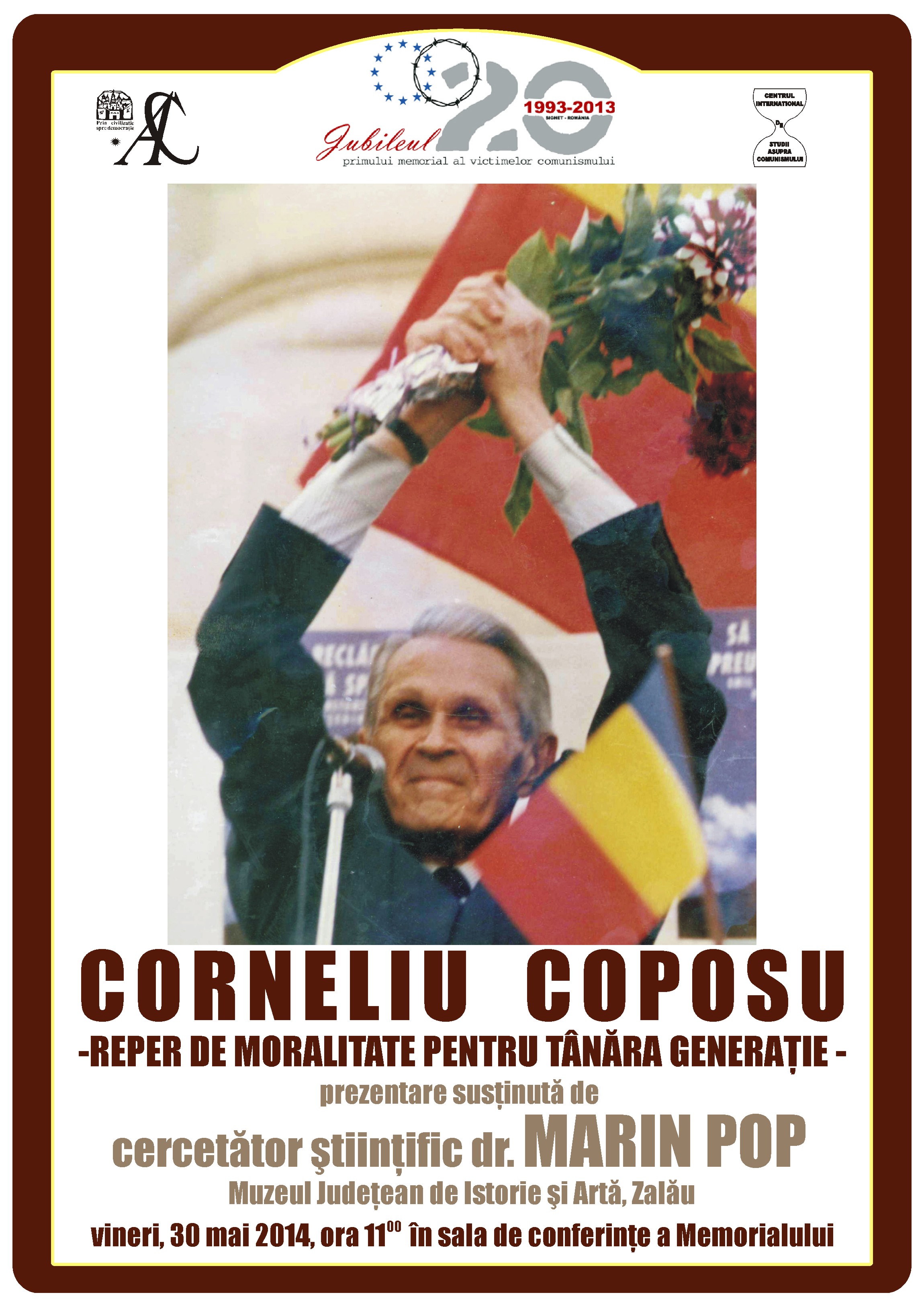

Chapter III The Political Man

The Institution – Leader

Corneliu Coposu proved to be more than a political man, he was an institution. In order to see how he became that, we shall have to start with…the beginning. In the phase of gregarious community, virtues or, as appropriate, inabilities acquire macroscopic valences. The simple life, of a primary community, can rapidly devote or, as appropriate, destroy any myth.

In 1962, in the Baragan Plain, at Rubla and the Calmatui Valley, were deported the most known “enemies of the people”. Ad hoc communities, far from the tumult of the socialist slogans, of the anticapitalist propaganda, the hundreds of H.D.-s were born for the second time, but this will also be the place of a baptism, that of Corneliu Coposu, a group leader, active and authoritative, the future moral leader of the anticommunist opposition. At the age of 50, the one who had started his journey on Golgotha at the age of 33, the age of Jesus Christ, will acquire in Baragan the role of a catalyst of the confused energies, an unquestionable moral landmark.

Corneliu Coposu was bearing the experience of the 15 years and a half of hard prison and the halo of the fighter who had never accepted to make compromises. The house arrest at the Calmatui Valley was a unique experience, following a detention which was as unique, 15 years and a half of hard prison. “For me and other detainees it was a blessing, because, if we had passed from the hard conditions in prison directly to a normal life, it would have been a shock tolerated with difficulty.” Remembers a few decades later Corneliu Coposu. (Viata lui Corneliu Coposu, p. 88)

Besides learning again the simple existence, the austere but invigorating life, close to the life of the world’s first colonists, the deported had the occasion to learn again the advantages of the family life. Corneliu Coposu had the chance of seeing again his mother, Aurelia, who stood by him in the isolated locality in the Baragan Plain for six months, as long as the Security allowed her. His mother’s presence would heal many of the imprisonment wounds and pull him out of the apathy and the political convalescence.

Baragan was also the place where he found again the big family, the last survivors of the camps, the past and future adversaries of the communist regime, Ion Diaconescu, Ioan Huiu.

A few months after settling down in a small house in Baragan “, it is signaled that he rallied behind him both elements that activated in the NPP and elements with an inimical activity of another kind”, as it results from a Security informative note on the 30th of March 1964.

House arrest turns Corneliu Coposu into an unquestionable leader. Mainly, because of his qualities of a good organizer, “he is an intelligent man, a communicative nature, a little too lazy and stubborn at times”, registers agent Preda Viorel in the note written on the 9th of June 1963. Agent Eugen Stanescu informs that “in Coposu Cornel’s house people come and go and he is never alone”, and he attracts his guests into dialogues with political topics. “All these discussions are listened to with interest because of the fact that Coposu Cornel includes some jokes, ironies in his stories, which attracts the others’ attention.”

At the end of the period of compulsory residence people were already talking about “the Coposu group”. In the note on the 16th of March 1964, agent Cistescu Nica registered that “the Coposu group continue to be starry-eyed and still have interest for national peasantry, making proselytism and asking questions about one and other’s political affiliation.”, the Security employer drawing the alarm signal that “the way their group remains leaves the impression of a party”.

The repeated refusal to deny his own past and his former party colleagues reconfirms, year by year, his leader halo.

In an informative note since March 1968, it is mentioned that two Romanians with the residence in France “consider Coposu Cornel a representative and genuine spokesman of the NPP for both the young and the old. This idea is also transmitted by the emigration”.

The Security Services are alerted day by day, especially because meanwhile Corneliu Coposu has refused two other offers coming from the communist officials, those of publishing in Glasul Patriei (The Voice of the Country) and in Scanteia (The Spark), motivating that “he does not want his signature to appear in the current publishings”. A simple signature in the semi-official newspaper of the Romanian Communist Party (RCP) would have saved him from many nuisances and would have given his watchers a feeling of restraint if not of panic. He refuses and dedicates himself to humanitarian actions, offering food, money and medicines to some hospitalized needy people. The quasi-unanimous opinion of the Romanian anticommunist resistance in the country and abroad is registered in an informative note since 1969. “Materials have been obtained from whence it results that various people who had functions in the NPP appreciate him as an incorruptible man, considering him the future leader of the NPP”. Two other decades will have to pass, which Corneliu Coposu will cross slowly, devoted to the vow that he made to tribune Iuliu Maniu in jail.

Meanwhile, the Security made 27 searches at his house and he had to give hundreds or even thousands of declarations. “I think that between 1968 and 1989, until one day before the Revolution, I was called hundreds of times at the Security headquarters and I gave thousands of declarations relating to my real or apparent anticommunist activity. I was accused of sabotage, of organizing plots, of actions aimed against the communist regime. Meanwhile I had 27 searches, occasion with which I think I had a quarter of wagon of manuscripts, correspondence and books confiscated. I still keep the reports and the warrants of presentation at the Security for inquiries.” (In Amintiri (approx. Memories), p.32)

A permanent harassment, doubled by a quasi-permanent watching, a non-stop stakeout, including microphone installation in his house. During this entire period of time, the Security sources confirm in 1963, “he has inimical activities”, in 1970 “he continued to have inimical manifestations” and afterwards his targets aimed not only the party but the presidential family as well. “He was inimically manifest, several times, against the superior party leadership and the members of the presidential family”, according to what a source relates in April 1985. (see Viata lui Corneliu Coposu, p. 122)

About Political Creed, Ideal and Optimism

The political creed is a character trait difficult to measure, but it seems that in the Senior’s life it was the dominant note. It was a permanence of his existence and its deep roots can only be found in the history of Ardeal and of his brilliant predecessors. In a conference about native Salaj he says that “The history of Salaj is an endless chain of oppressions, from clew to earing, of pain and revolt the other way round. The Romanians in Salaj lived long and hard centuries only with the strength of the memories, of the power of faith and of the conscience of their eternal right of mastery.” (In fata istoriei p. 303) “It must be otherwise too”, was Simion Barnutiu’s creed.

In January 1952, (in Viata lui Corneliu Coposu, p. 65) informant Busuioc reports about Corneliu Coposu; He congratulated me on New Year’s Eve and wished me urgent freedom, claiming that 1952 is the year when the destiny of mankind for the following 1000 years will be decided. The Destiny of mankind for the following 1000 years, probably a joke, but full of meaning. His overflowing optimism probably inherited from his mother Aurelia, was weakening the torturers but made them more humane. There is a crescendo of the punishing and suffering of the 17 years and a half.

Informative note since 1968, (ibidem, p. 99) informant Sultan, “Coposu made the statement that the events in Czechoslovakia are the beginning of the end of communism in general. He is convinced that the economic and ideological bankruptcy of communism is total (our emphasis) and that the forces that will overthrow it, will be born within it and they will not come from the outside. A prophetic but mostly stimulating statement. Besides the deep meaning of the internal combustion of the crisis of communism, it also stands for an invitation to action. His attitudes are also related to “the ideological faith”, a beautiful and comprehensive term, a notion suitable to the Senior and to his life ideal.

About Faith and Ideology

The Senior’s vow will guide him his entire life, results from an informative note since October 1971, the source Ghioca, (ibidem, p. 102). “Coposu made in front of the source the statement that in 1974, with the occasion of the Tamadau business, he was in dr. Jovin’s house together with Maniu surrounded by the authorities. (…) Maniu told him in private “you are like my own child, maybe one day in my place too, no matter what we shall go through don’t you think for a second about leaving the country. I am sure that I’ll end up in a communist prison”. Coposu states “I made the vow and I shall be loyal to him all my life.” These confessions made to an informant-“friend” are more veridical and profound than any further texts, a test of life.

Corneliu Coposu was convinced that he had a mission to accomplish. Such statements would seem venturesome if they were not sustained by other confessions. In 1953, after the expiation of not even half of his penalty, in the Vacaresti Prison, on a bed in a cell, charged with murder, Corneliu Coposu plans the organization of post-communist Romania. “Destiny, a Ioan Lupu confession, (In fata , p. 358) made that I meet Corneliu Coposu again, in 1953, in the Vacaresti prison where we did our best to share the same cell. (…) Days, weeks and months, standing face to face on the bed that stood for our life space in prison, we would discuss all day long projects that would contain plans for the political future of Romania, blended with commentaries on the historical events that we were living, surprising the people around us that we had the patience to talk to each other for hours every day.”

A page of political philosophy in a Security note since May 1979, the Security informer relates that, when simply ran into on the street, Corneliu Coposu said that “Nowadays, in Romania, one cannot really scrape together with anybody an action for fighting or crushing the communist regime (…) Luckily, C. Coposu is certain that this regime will crush by itself, getting old and wearing off maybe faster than we think as all the totalitarian, based on force regimes”, p. 114-115, etc. an extremely lucid vision in a moment of political relaxation and economic revival, of economic increase of the system.

Besides, the sources confirm what is known from previous confessions, but certify what crossed his life as a red line, his passive resistance, “my passions are limited to reading, bridge and chess issues”, a declaration given at the Security in 1982, but with precise goals. The source I. C. Dragan reports that the objective CORNEL “was inimically manifest, several times, against the superior party leadership and the members of the presidential family”.

Iron Guards and Communists

We cannot include Senior Corneliu Coposu in the epoch without deciphering, even if roughly, the position towards two ideological systems which marked the epoch in which he lived. At an age close to these ideologies fell victim the future great men of culture, Mircea Eliade, Eugen Ionescu or Emil Cioran.

“I could never have hard feelings for other people because they were Hungarians or Jews”, he confesses in a post-December interview. (see In fata, p. 190). I had iron guard friends. But I have always considered their mysticism and fanatic nationalism a little too childish. The great vogue of nationalism appeared somehow logically. After the beautiful union of Romania, the youth woke up without ideals. The generation called “The White Lily” appeared, Eliade, Noica, Cioran, Tutea and others. All of them were rightwinged, not necessarily iron guards. And among the iron guards there were also both paranoid people and honest people, but I found their manifestations silly. There were also many girls in the Movement. All of them, ugly and full of complexes, would reach a place where they were given importance.”

In his opinion, the same thing happened with the communists. “It was the same thing with the communists. It was about the wish of being noticed”. (ibidem). A right wing appeared even in the party that he served, the Vaida Voevod line, of which Iuliu Maniu outdistanced. Corneliu Coposu remained loyal to the Maniu line, roughly kept even after December ’89.

About Communism as a Historical Epoch

Corneliu Coposu treated communism as a short and inefficient experiment. “I have always had the certainty of the fall of communism and its country, but I expected this to happen much earlier”, he confesses five decades later. (see In fata istoriei[1], p. 82)

He had the curiosity of becoming familiar with the communist ideology from the inside, not from imported communists, but from the source.

In an article appeared in the Dreptatea newspaper[2], on the 26th of May 1946, entitled Talking to a communist, (ibidem, p. 51), Corneliu Coposu reproduces a dialogue with a genuine communist of the year 1946, in a moment when the Soviet occupation troops were in the country. His dialogue partner “an honest man, with convictions acquired through studies and consolidated through renunciations and suffering”, but, as we shall see, cynical and unscrupulous when it comes to Power and, mutans mutandis, deprived of patriotism. “I respected his courage of honest opinion, the brutality of confession which most of us avoid and the sincerity with which he defended an ideology that we thought it was so wrong.”

“I admit that we are a meaningless political minority. But we shall accomplish electoral majorities”, the left winged advocate confesses, mentioning at the same time the methods through which the Communists will access the power. On the one hand, by creating a maneuver mass made of “traitors, political swindlers, collaborationists, all in all the rottenness of the Romanian public life.” On the other hand, by applying the principle that “the crowd must be stirred, even against its will”.

What kind of political ethics absolves you to organize the Terror and the political persecutions, the intolerance and violence which have nothing in common with democracy?, would have asked Coposu. “There is no morality in politics, the communist activist mentioned, the class and party interests come first” and consequently, the author of the interview mentions it is legitimate and there will be applied the entire arsenal of class fighting, beatings, assassinates, organized terror and other condemnable means of taking over the Power!?

About Nation, People and Providential Men

“History is not written by the resigned but by the audacious. Nations live through them”, the 23 year old young man wrote prophetically in 1937, in a confused historical period. It was a historical moment of vacillation, confusing for the young, wisely characterized by the young man who was at the age of his first lessons of political culture, of initiation as a zoon politicon. We live a moment when “an entire nation starts to shake and weaken. A suspicious, illegal element slides in the simplest relations. Qualities are negotiated in an unhindered way. Virtues borrowed the mark of anachronism. Everything depraves. The liveliest, the most judicious spirit is lost in Byzantine subtleties” (…), and “all the composition is heading to plunging. “ (The Corrective of the Paradox, In front of History[3], op. cit., p. 476-477).

“The most terrible slapping of the human dignity is the chain” used to say with a painful premonition the son of the protopriest of Bobota, but there comes a time when “common people don’t feel its shameful shackle. Habit wears off sensitiveness.” Corneliu Coposu depicted with a lot of plasticity the sad icon of the years before the second great world conflagration.

“There are dark ages in the history of each people, during which the entire aggrieved nation crawled helplessly its chained feet on the road of moral renunciations.” It is the moment when the providential men of the nations must enter the scene, “the men of honour and courage”, the audacious ones. But “sometimes the decades, even the centuries, are stingy with names of tribunes.” THE TRIBUNES, because they are the ones that we are talking about “are usually rare and in a small number, the ones who choose a different way from the one that the crowd craves for. For such deviations, a big dose of political sense and an even bigger one of heroism are necessary.” The leader, the man great indeed, “is like a meteor which shines and consumes itself while lightning”, only that “the crowd does not always have the power to declare solidary with him, to fight by his side, to sacrifice at the same time with him”. (ibidem, p. 477)

Therefore, there are worthy crowds and less worthy, cowardly crowds. In the first case, the only one that young Coposu takes into account “there are great epochs, where the majority, if it is worthy, draws nearer to the way of life, to the way of the dignity of the nation, and goes on the bright line of history, next to its CHOSEN MAN; in other epochs, - if they are cowards, - the majority turn away from his way, more difficult, more dangerous than others, he is the nation itself; he speaks in the name of history”, says Corneliu Coposu who concludes like a genuine democrat that even in the case of the cowardly crowds, “the leader has only one duty, besides that of following his destiny; the duty to convince the crowd of his justice”.

The history of Romanians is full of examples of men of honour and courage. In an essay published four years later, “1848”, he sent “humble feelings of submission to the Blaj of the three national gatherings in 1848, to Iancu’s cross which guards the height of the hill in the north, to the Plain where the rush of the delivering revolt was leavened and to the Rock of Liberty, pervaded by the historical shivers of our tragic aspirations.” “Mentioning them is an act of integration in the pride of the past of whose loftiness our generation proved to be so unworthy, and an act of verification of our destiny in order to face the dark future”. The heroes of 1848, “the dead from the past remain beyond death the guides and guardians of the Romanian destiny”.

“Dominations and reigns are temporary. The worthy nations enjoy immortality the nations go ahead, over obstacles, on the way of their destiny. The predecessors’ greatness blends with the life of the present and of the ones that are to come”, Corneliu Coposu explains the victories of the past.

Against those who commit crimes on behalf of the people, “the defenceless walls are painted with urges to crimes, with capital sentences dictated by “the people”. The real people is another one, “in front of these little people, disguised in the toga of the prophets of the future, stands up our nation, that stays unflinchingly in the position of the great commands of the Romanian destiny; the real people stands up with its entire virtue, with the conscience of its rights, with the determination to protect its peace and home”. (ibidem, p. 39)

What is a people? “The people is not a crowd, the people does not lurk on hidden lanes with a loaded revolver. It does not deal with devastation either”, writes Corneliu Coposu who is convinced that “the longing of destruction, the ferocious hatred, the political crime are unknown to the soul of our nation.” (op. cit., p. 38-40) Hence the organic need of Freedom. Because “the real freedom is the transposition in the political ground of the biological need of motion. The right to do what you want, within the limits of the law, without any external constraints, or not to do what contradicts your convictions, is called freedom”.

His conclusion is natural “The nature of the Romanian people is begotten of sun and freedom. In order to lead its life authentically and honestly, with love and diligence, our People needs freedom. Freedom itself is the spiritual foundation of the Romanian people”. (op. cit., p. 46)

The Complex of Dishonesty

Corneliu Coposu lived in the communism period like his ancestors in the enslaved Ardeal. His convictions remained unchanged; they rather fed with the ideals of the Suplex Vallachorum epoch and of the Revolution in 1848. He remained dismayed to see that after four decades of communism, the Romanian people had another moral profile. Cooperativization and the peasant’s separation from the land, the forced industrialization, the systematic indoctrination made the man in the street change his identity. The idols of communism took the place of some moral features that had consecrated the Romanian people. For the common man, duplicity and lying, means of resistance at the beginning, will become a way of living. And since habit is a second nature, in four decades and a half, mentality had changed exceedingly.

“The 45 years of communism inculcated in people’s minds the complex of dishonesty. Two generations that were born and brought up under the communist regime, were educated under the aegis of the lie. These people knew that one had to think something and express something else. This complex is still present. (…) unlike this category of people, I had the luck to stay in prison while the population of the country was practicing the complex of dishonesty. I did not assimilate it and I believe that the obligation of a person responsible of a certain political situation is that of being honest and firmly affirming his principles, without making small calculations over the opportunity of an attitude”, he says in an interview appeared in June 1994, with the natural conclusion that “principles are not negotiable”, opining that “the most suitable democratic shape for the difficult events that our country is facing, is the restoration of the Constitutional Monarchy.” (In fata istoriei, p. 198)[4]

About Principles and Morality in Politics

White Lilies and Pelargoniums at the Window

Life and politics are two expressions of the same conscience. The righteous man and the clean conscience are part of the totality of virtues of the great men of the nation. “The righteous man does not listen to the voice of conscience”, Corneliu Coposu wrote a fragment of Plato’s Dialogues. His conscience cannot be shaken neither through the infamy thrown over him, nor through persecution. He will walk, unflinchingly, until his death, on the paths enlightened by this conscience…” Prophetical words which will be his shield and guide along his entire existence.

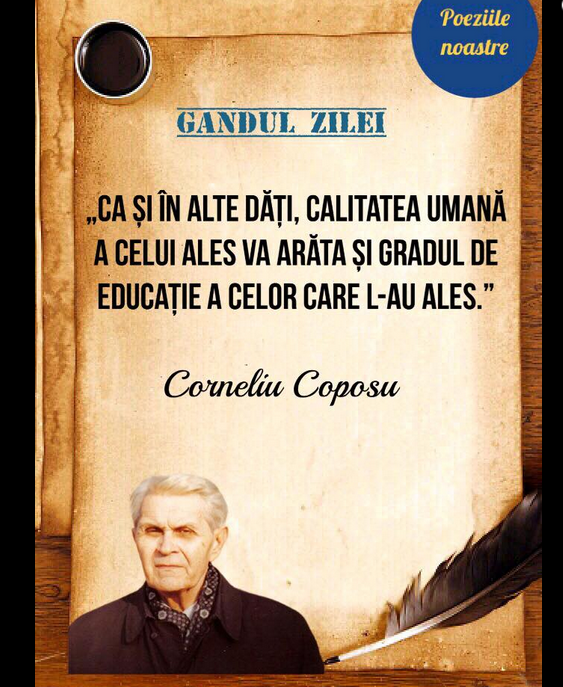

“Principles are not negotiable. The conceptions of those who define politics as a chain of compromises, although they can find correspondences, lead nowhere. The ethical element must prevail in the political life too. Respecting your own principles is a sine qua non condition of a person who wants to be a political man, not only a politician. (ibidem, p.10). His entire experience as a political man, but also of the dozens of tribunes who sacrificed their lives for an ideal, is concentrated in a few phrases.

The political man must listen to his own conscience but also obey the Dictatorship of the principles. “As far as principles are concerned, of course it comes many times to compromises on a tactic line and on strategy. But the moment one makes a compromise on the line of principles, this is condemnable.”

The providential man must be “incorruptible, mystical and moral”, according to the portrait made to Iuliu Maniu whom he considered in an interview for Tineretul Liber[5] in 1991 “the brightest expression of the authentic Romanian spirit in the interwar period and the exponent of the real tendencies of Romanian independence under all circumstances, in all conditions”, and as an ideal, democracy based on law, politics – on ethical principles. Corneliu Coposu is convinced that “man without faith is not a complete man”. This is only one of the reasons for which he made an option for Christian – Democracy.

“I consider that without pelargoniums at the window, that is, translating in a free language, without consistency and morality, valid politics cannot exist. Of course, there can be, under special circumstances, the pseudo-politics made by some people who are only bound by the pragmatic interests of the moment and who have no other preoccupation but the prolongation of their agony, of their political rule” (from an interview appeared in 1994 in Viata Buzaului).[6] Political men do not till pelargoniums at the window, “they favour vanities and tendencies of prolongation of a terrible agony of the country.”

His poem written in prison, Ruga[7], sums up a part of his life philosophy:

sift, dear God, the peace of oblivion

over the endless pain

sow fields of faith

and enhance the dew of ruth

plant, dear God, love and lilies

on the field flooded by hatred

and lay over the mountains of dross

peace, forgiveness and serenity

[1] In fata istoriei(approx. In Front of History)

[2] ziarul Dreptatea (the newspaper Justice)

[3] Corectivul paradoxului, În faţa istoriei (approx. The Corrective of the Paradox, In front of History)

[4] In fata istoriei (approx. In Front of History)

[5] Tineretul Liber (approx. The Free Youth)

[6] Viata Buzaului (approx. The Life of Buzau)

[7] Ruga (approx. The Prayer)