Motto: “There is neither mercy, nor sympathy for the enemies of the people”

From the Number-Detainee, to the Institution-Leader

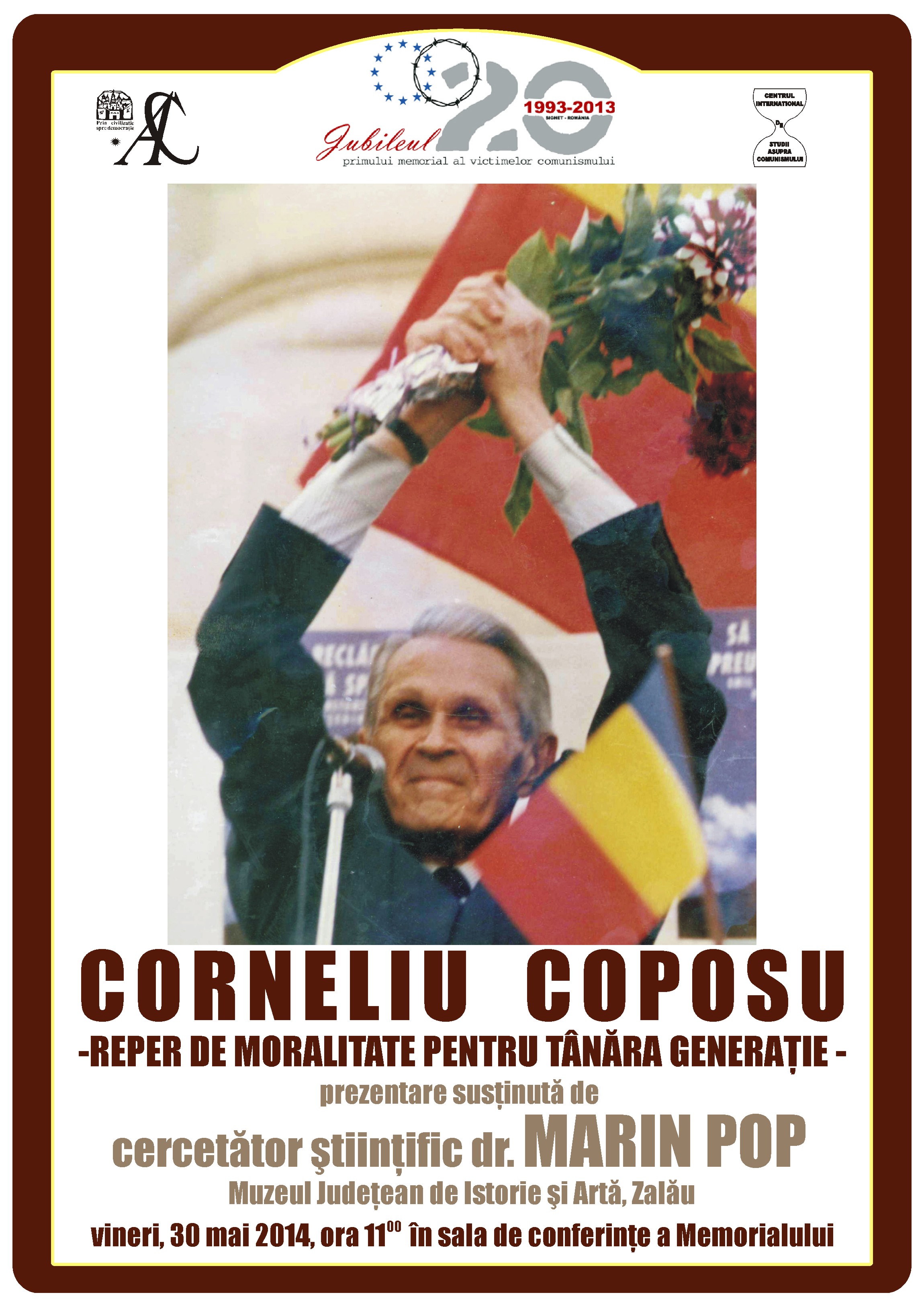

Whoever had the honour of personally meeting Corneliu Coposu, surnamed the Senior, can consider himself or herself a happy person. Whoever knew him closely, listened to him, drank from the springs of his knowledge and understood the voice within him, can consider himself or herself a lucky person. Such people are born every few hundred years!

People are born in Romania too! Romania itself can be considered lucky with such a personality. Corneliu Coposu died as he lived, righteous, unflinching, like a soldier on duty. Only that his duty was prolonged over more than six decades, out of which 17 years spent in maximum-security prisons, charged with the crime of intense activity against the Romanian people. He patiently expiated his punishments, with faith in God and in the divine justice. He was and remained an incurable optimist, a providential man, but he despised fortune, honors and any kind of function. The number-detainee, “the bandit” without an identity, deprived of the elementary rights of any human being in the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary since the 50’s, bore stoically other three decades of oppression, becoming the leader of the democratic opposition of Moral Romania, one of the models of modern Europe.

“Many experiences that I have had are so incredible, that it seems impossible to make someone else understand them. A common person, unused to the treatment that the communists used to apply to us, might not believe you. I would think at times that not even I would not have believed my own story if somebody else had told it to me.” (interview, Romania Libera — (approx. Free Romania) is a national Romanian newspaper —, 1994).

This paper is a simple “attempt”, for personal usage, to figure out the springs of the thought and deeds of this singular personality, their internal combustion, their value for the future generations. A small country like Romania cannot resist the challenges of History otherwise than by means of exemplary people. Corneliu Coposu, we want to demonstrate, as if it were still necessary, was one of them. Because he said in his speech at Alba Iulia on the 1st of December 1990, “only worthy nations are eternal”

Chapter 1 ROOTS

The Son of the Protopriest of Bobota

Corneliu Coposu had a complex and marked by the unpredictable existence starting with his adolescence. Born under the Taurus sign, the son of the protopriest of Bobota learned the first lessons of patriotism in his family. From his father, from his grandfathers.

With his typical modesty, Corneliu Coposu considered that “my biography lacks importance and interest”. The research of the archive brings numerous disclosures. His father, the Greek-Catholic protopriest Valentin Coposu, was in his youth a great fighter for the Romanians’ national unity. His political activity brought him imprisonment, during the Austria-Hungarian regime, for “high treason”, in the prisons in Vat, Seghedin, Budapest and Nirekhazo, from where he was released by the Romanian army when Budapest was occupied. His paternal grandfather, Grigore Coposu, was the right hand of the president Gheorghe Pop of Basesti and took part in all the national fights in the epoch before World War I. He was seriously ill-treated on the occasion of the elections in 1906 when he also died. Corneliu Coposu characterized him as “a remarkable Romanian public man on the political scene of Ardeal, of Transylvania under foreign occupation, although he died young.” His maternal great-grandfather, the Greek-Catholic protopriest Iulian Ancean of Ciolt, was one of the toprankers of the old National Romanian Party in Hungary, a personal friend of Ilie Macelariu and of the front rankers of the party of that time. He militated for political activism at a time when the orientation of the party was the pacifist conception.

Therefore, a lode of the inborn activism appears on both a maternal but especially on a paternal line. An authentic militant, from generation to generation, with roots of almost one century. Besides that, a co-regionalist exclaimed thrilled after he had personally met Corneliu Coposu in the 90’s: “I had the thrill of the presence of Simion Barnutiu’s spirit every time I was around him. There was, in Corneliu Coposu, the same soul of the love for people, for the Romanians persecuted by the nation, that strong belief that any oppression would end at a point, that things can be different.”

At the age of five, little Corneliu is enrolled at the school in the locality, a Romanian confessional school kept up by the church. There are years marked by important national and European events, but also by the effective, cultural, political and economical completion of Great Romania. In 1923, Corneliu Coposu is already a student at the St Basil the Great High school in the Blaj of high expectations. A high school which enrolled 1400 students and which he graduated successfully. At 16 he was already a student at the Faculty of Public Law and State Sciences of Cluj and after graduation, in 1934, he applied for candidacy for doctoral degree which he was awarded three years later. At 23, with solid studies in Law he chose his own path. “I was passionate by politics, Corneliu Coposu remembers, and I chose my judicial career despite my father’s approval who wanted me to be a technician at all costs.” The mirage of politics was greater than any universitary career. “I became a lawyer stuck at the middle of the career. I also had a universitary career – at the Faculty of Law, at the Penal Law department” (Corneliu Coposu, In Fata Istoriei (approx. In Front of History) , Metropol Publishing House, 1997, p. 238)

Meeting Iuliu Maniu was decisive. Maniu as a person, despite all his polical descents out of which he knew how to replicate elegantly, irreversibly entranced young Coposu. Unconditionally, he became his disciple and remained so until his death. “Maniu’s nephew” was the nickname that he proudly carried from prison to prison.

The manuscript of a book, A Tribune’s History, prepared for printing, but confiscated and destroyed immediately after his arrest in 1974 was re-written of fragments. “An upright, mystic and moral man”, “He is one of those who never yield; whom only death can defeat” are only some of the features of his portrait from 1947. “Maniu was the brighest expression of the authentic Romanian spirit in the interwar years”, he says in an interview in 1991.

Corneliu Coposu entered right footed in the big politics. At the University of Cluj, where he was also awarded the doctorate in Law, he was chosen president of the Democratic youth, so that in 1937, at the end of his studies, he joined irreversibly and irrevocably the president of the NPP (the National Peasants’ Party) . Between 1937 and 1940, in a period of great historical convulsions, the former boxing and weight lifting champion from the time when he was a student, was taking care of the personal security of the NPP president. In 1945, when he was 31, Corneliu Coposu was elected deputy secretary of the party and, in 1946, secretary of the permanent Delegation of the NPP, and Iuliu Maniu’s right hand as long as the entire world conflagration lasted.

The Eloge of the Predecessors

Stoicism is a frame of mind, a philosophy that can be depicted from the life examples of the predecessors, considered thoroughly by the means of assiduous study and strengthened by means of exemplifying deeds. The chosen drank almost entirely from the springs of wisdom, without even pronouncing their names, and lived exemplarily in their turn. Corneliu Coposu, the son of the Greek-Catholic protopriest of Bobota, knew the writings of the ancient philosophers Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius and Seneca. But probably he did not even need to. The Ardeal of his times gave to the country a Marcus Aurelius, that is Avram Iancu, a Socrates, that is Iuliu Maniu, the sphinx of Badacin, and an Epictetus, that is Simion Barnutiu, the revolutionist on the Plain of Freedom. But what more substantial models than his grandfather, Grigore, or his father, the clergyman Valentin Coposu, both imprisoned for high treason of the Hungarian government.

In his youth writings, Corneliu Coposu foreshadows happily and convincingly his future behaviour. It contains, in nuce, the entire route of his life. Chance and genius co-existed and “the ideological faith”, a wonderful expression, kept him awake even in the darkest moments of his life.

During his teenage years, Ardeal was a region which was sacred and sanctified by exemplary historical deeds. His father was the first example. The protopriest of Bobota dedicated his life to the emancipation of the nation, he suffered in the Hungarian prisons so that his descendants could be free, and he wanted his son to embrace a technical career, not a political one.

The Salaj County, where Corneliu was born was full of advising deeds. The exhibition of Transylvanian personalities opens right in the native Salaj. Three neighboring localities, and a total of four, Bobota included, the name of all of them starting with “B” offered this country great names. Bocsa, Simion Barnutiu’s village, Badacin, Iuliu Maniu’s village, Basesti, related to George Pop of Basesti, and finally, the village where Coposu Senior was born: Bobota. “There are four villages, whose names start with the same letter, four villages blessed by God”, remembers Grigore Lapusanu – Transilvan, an inhabitant of Salaj, a few days after the demise. (ibidem, p. 397)

The portrait of the patriot politician is rendered with a lot of plasticity in one of the Transylvanian Busts, Victor Deleu, the president of the Transylvanian volunteers. Young Corneliu Coposu believes that the great Transylvanian established “the schedule of his life” following solid principles. “A man descending from a stone hard race, he was the grandson of a fine commander from Iancu’s revolution: Iacobescu, the fighter from Salaj in 1848”. His face has the features of a true patriarch: “Kind and calm, wise in everything, Uncle Victor lived calmly and temperately, with a life discipline that promised hoary old age”.

“Good thought and deed were the same for him”. Therefore, an austere but active figure, characterized by honesty and integrity, “he was, above all, an example of honesty and integrity”, a good leader, “he proved good skills in organizing and received public gratitude as a result of the functions of secretary of resort interests and mayor of Cluj.” Courage, kindness and, most of all, modesty are added to these qualities. “After the Union, he honored with his fruitful work many reliable high positions, but he never took off his coat of modesty, he never wanted more than he was given.” He remained related to his native region, the Salaj County, which he represented in “the house of the Country”.

In his public life he was guided by “the olden law of decency” (Transylanian Busts, Victor Deleu, article published in Ardealul in 1940, ibidem, p. 18). Briefly, Victor Deleu meant “a strong character”, in his first youth “he swore to serve a conviction and an ideal” a way from which “nobody could turn him around” and his end was like his life: “He lived and died on duty, a living, unforgettable example for all his followers.”

Another bust, written in 1940, when black clouds were threatening the Romanian people is that of “the good shepherd”, Bishop Nicolae Ivan.

Corneliu Coposu uses various stylistic devices to underline the loss of “one of the best Romanians”. “He has, behind him, a life of martyrdom and fight (…) A representative of the generation that carried in its soul the voice of law, with its promises and expectations, the Bishop of Cluj was honored by the joy of righteous Simion, of seeing himself the ascension of his church and the salvation of his people”.

Bishop Nicolae Ivan lived “with Margineanu’s unshakeable perseverance and intelligence, with true love for his nation, endowed with unsurpassed knowledge of people and things, with the most distinguished passion: the passion for labour – the great founder revived, in the heart of Ardeal, from the ashes of historical memories, a Romanian Bishopric.”

Vladica Nicolae Ivan, “the unsurpassed master who wrested an accomplishment from each second”, “fought, with uncurbed boldness, with rough wrath but with Evangelic kindness against all Romanian sins and low ebbs”. Nature itself deplores the shepherd who blessed “his Nation and Law”. “On the snowbound city of Cluj, the sad bell hymn crosses the sky, blending its dark message, in concord of grief, with the voice of the mourning Troparions…”, this is the feeling that the young politician experiences at the death of a great Romanian.

In 1936, when he was writing the second portrait, Corneliu Coposu was 22 years old. Now he establishes two of the landmarks of his political creed, respect for NATION and respect for LAW.

Corneliu Coposu created numerous busts of “the worthy men of the nation”, but that of the “tribune” Iuliu Maniu is, by far, perfect. The life of the son of the protopriest of Bobota borrows the qualities and the moral traits of all his characters, but as far as Iuliu Maniu is concerned, “a man that is born only every five hundred years”, as he confessed in a post-December interview, he resembles to him so much that they seem to merge.

The sphinx of Badacin was a role model for young Cornel, the Transylvanian politician’s shortcomings and blunders do not seem to have influenced him in any way. On the contrary, being around him when he made the most difficult decisions, some of them historical indeed, Corneliu Coposu understood his springs and tried to imitate him, even in small cakes and ale. The heavy smoker comments: “He doesn’t smoke or drink. He doesn’t have any brutal or self-intoxicating passions. Neither his moods, nor his senses control him. Wealth doesn’t tempt him. His life standard remained unchanged. Soberly, modestly, naturally – he lived, for the past 45 years, the hard-working student from Vienna, the deputy of Vint, the famous lawyer of Blaj, the prime-minister of united Romania and the recluse from Badacin (…) The brightness and the honours, desired by many, came up against an immunized Maniu. A portrait sketched when he was young which will decisively mark the one who was surnamed the Senior of the Romanian politics.

And the descriptions will continue the same way, as Maniu was part of “the few great people who were not overwhelmed by passions”. This “incorruptible, mystic and moral man” “is immune to threats. And not even the obvious danger can shake him, can turn him away from his duty. Courage is the decisive denominator of all his calculations”, “a cool, calculated” courage, based on “the merit of victories and popularity”, “the supreme argument in the important political moments”.

His weapons, like his predecessors’, are the love for the Romanian people and the democracy based on harsh law. “He is probably the only political ruler – destined with the features of a chief – who understood to carry out the role of tribune of the nation, restricting his hearty genius of emperor in the crust of an exponent of democracy.”

“Other leaders can symbolize happiness, copiousness, humaneness, optimism, wisdom. Maniu is the law! He stands, by excellence and above all, for harsh legality. Alone. Brilliantly and perfectly…”, this is the sketch of the portrait of the tribune Iuliu Maniu for whom Coposu infers the triumphant end. “He is one of those who never yield; that can only be defeated by death”.

Portrait Sketches

Youthfulness Portrait

Gabriel Tepelea met young Corneliu in 1933 at Cluj, when he was a student, an editor at the Romania Noua (approx. New Romania) publication in whose pages he presented polemics “with the right wing fueled by the international context”, and an active participant to the Study Debating Society of the National Peasants’ Party. “I can see again the Corneliu Coposu of that time: tall, well-built, with wise eyes, very communicative, favouring friendship out of an inner impulse” the famous man of culture remembers him.

In a book published in New York, N. Carandino makes one of the most concise and eloquent presentations of young Corneliu Coposu. “He had humour, he was lively, generous, talented and had character without feeling the need of showing it every second. He always ignored his personal interest and despised current vanities. His modesty was strong, his word was pledging. For such qualities he had obtained Maniu’s appreciation and complete trust.”

In an article about “the dissidence by means of sport” of prince Serban Ghica, the writer Corneliu Stefan, a very good friend of the rugby-prince, wrote in 1992: “One day, on the stadium in the Child’s Park in Bucharest, he introduced me a tall, pale gentleman, who had movements of internalized civility, like a quality of blood, with a frozen, sad, barely smiling mimicry. I kept in mind the remark of the rugby player. You see, he exceeded us all, he stayed in jail the longest, under both the previous and current regimes.” The event took place in the 70’s when prince Ghica, the Senior’s best friend, as we shall se, was leading a rugby team in Buzau where he also worked on a construction site. Besides, as a fate irony, – destiny decides that great men help each other – Constantin Ticu Dumitrescu enters this equation. Prince Ghica, the chief of a construction site in Buzau at that time, helped the latter to get a job at a branch of the firm in Dumitresti village, Vrancea County!

Rodica Coposu, the senior’s sister, considered Bani Ghica her brother’s best friend. “In his group he was, first of all, his best friend, a life friend next to whom he endured both the good and the bad, Serban Ghica or Bani, as we called him, who honours us with his friendship due to his exquisite friendship with Cornel. He was his closest and most devoted friend and this is how he remained.” Rodica Coposu continues her idea with the miscellaneous chapter, the political friends. “There were, of course, his political friends that he used to meet.” The Diaconescu family were omitted, of course, who, according to the Senior’s testimonies in the security files, “used to visit us 3-4 times a year.”

Who was the mysterious Bani Ghica? A direct descendant of 10 rulers who outlined the destiny of pre-modern Romania, king Mihai’s future classmate had a tumultuous and full of adventures life.

“Friendship, fair play, zest, loyalty and courage”, this is how his long live friend, Corneliu Coposu, characterized him. In a spontaneous sketch, destined to a Bany Ghica’s portrait, he blends humour with tragedy: “The diminutive Bany comes from Serban, the name to which his baptism godfather, marshal Averescu, added his own name, Alexandru, but there are few people who know him otherwise than Bany. Bany is in our society in Bucharest, in the entire country, unique, he is almost a notion which means “friendship, fairplay, zest, loyalty and courage”.

Bany was in his youth a fan of the oval ball sport. At 18 he became the youngest permanent player in the national rugby team and at 27 he was appointed, also as a record, the youngest president of the national rugby federation. This is the period when he recorded a financial success for this sport, leaving the famous “Rugby” stamp. In 1940 he went to England, to Birmingham, to complete his studies and after the war he became one of Iuliu Maniu’s private secretaries. From this moment on, the ways of the two friends cross. Despite his royal origin, Serban Ghica spent in prison seven years out of which two at the Channel together with Corneliu Coposu. This is how he describes the imprisonment at the Channel (see Prince Ghica’s Gulag Amintiri dintr-o alta eternitate (approx. Memories from Another Eternity), in Dorin Ivan, Amintiri dintr-o alta eternitate, Alpha Publishing House, Buzau, 1999). “I shared with Corneliu Coposu the most difficult moments in prison. We shared the same cell, a lock-up as big as a…stove. We were more connected than two twin brothers.” His memories from the Channel, where he worked on the same truck with Corneliu Coposu, are the most diverse. “The Channel was by far the roughest, prince Ghica remembers, general extermination was the objective, the food was not enough. (…) The more than 1000 wire workers from the Midia Cape endured superhuman labours without getting enough food. An apocalyptic famine ruled the colony. Demises were frequently recorded. All detainees tried to improve their food ration by eating all kinds of animals, dogs, toads or turtles, snakes. We would hunt snakes on the way from the train to the work place. Many snakes were run over by trucks and the most courageous of us would get out of the row and hide them under the zegheZeghe (approx. fur coat) is a Romanian word which refers to a coat made of sheep leather with wool on it and which is usually worn by shepherds.. At the work place they would squeeze the snake and take out the grease which they would spread on bread. Then, they would enjoy the raw meat for a long time.” Corneliu Coposu, a lot more athletic, helped him many times to avoid staying in the lock-up, by helping him carry out his quota. The two escaped sure death after they were forced to work under a cliff – thousands of cubic meters underground – which was on the verge of crumbling. They miraculously escaped thanks to Good Lord and Corneliu Coposu, whose objective was that of “sabotaging the production”. Proving workers’ discipline, under the cliff entered, in their stead, a team of informants that would watch them non stop in ex change for the illegal receipt of money and food. “Destiny wanted us, programmed to be pliant to some nuisances - that is days spent in the lock-up – in exchange for money receipt, to pull out under the debris, with the spades, pieces of the butchers’ bodies, heads and limbs… It was awful.”

What saved the two enemies of the people during all these years of political imprisonment? “Fear”, confesses Bany Ghica. “In jail I was prepared to face anything because I knew that I was going to… die. I defied death every time, because I was sure there was no escape…” (ibidem, p. 48-49)

Corneliu Coposu, whose incarceration was harsher, out of which eight years in complete isolation at the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary, is much more nuance. “The most useful was, undoubtedly, the hope. I say hope, not confidence, because I am a LatinistOriginally speranta (in Eng. hope) coming from the Italian word speranza, unlike the original word nadejde which comes from the Slovenian term nadežda. Hope for the days to come, hope for the future of Romania, hope for the fall of Communism. Besides, I have always been an optimist. I had a permanent hope, almost a certainty, that I would get out of jail – although I had become a ghost, I was barely standing – and that Communism would fall”, an interview published in Viata Buzaului The Life of Buzau, on the 21st of November, 1994. On the second place, from the point of view of the importance, was faith. “I have never had any kinds of flaws in my faith. A strong, powerful faith in God and in His justice.” Rodica Coposu suggests in the same publication that something more profound was in the middle. “He had a creed that he followed and gave his life for that creed because, even if ill, he did not spare himself at all (…). A lot of politicians entered politics for material thriving and for appointment to positions. He was never interested in that, he was completely detached of such things. (ibidem)

Serban Ghica, creates, on his turn, a portrait sketch at his death (in Corneliu Coposu, In fata istoriei (approx. Corneliu Coposu, In Front of History), p. 352). “Physically, he was a handsome man, of an impressive height and a very pleasant appearance. His kindness and decency were exemplary. You could never find a flaw in his friendship. I fully felt this in our 53 years of friendship. He was a man with a unique moral integrity which he made proof of until the end of his life. As far as politics is concerned, he also proved a strong sense of realism, following Iuliu Maniu’s trend. (…) I would like to emphasize that in 53 years of friendship, we did not have the slightest contradictory discussion.”

An Epistle of Love and Friendship

A universal history of friendship will probably be recorded in the epistle with SEWN LETTERS, a message on a cloth patch, written not with a pencil, but a sewn one, letter by letter, sent from jail, through a nurse, by Corneliu Coposu to his fellow-suffering, Ioan Lupu.

Besides, Ion Lupu considers the Senior “my most faithful friend” in “sixty years of friendship and 53 of intense activity” (In fata istoriei (approx. In Front of History), op. cit., p. 360)

”Ionel, we decide here, in the Vacaresti prison, to keep our friendship for the rest of our lives, to advise each other in everything, no matter how personal it may be, so that it can be useful for both ourselves and the Romanian people”. “This decision, made on a bed in jail, remained a sacred vow until God took his life. It was a strong friendship and as doctor Baican, who gave him medical treatment in Germany, declared: “I spoke a lot with Corneliu about his friendship with you and he told me that you were the only person with whom he could argue but the two of you would still remain friends.”

“In our private life, the friendship feelings were affectionate, but they were deprived of neither irony, which appeared in our moments of rest, nor of stories, when we would conjure up the years of our youth, of the incarceration that we did not regret”, Ioan Lupu remembers, who, just like his friend, does not regret the years of imprisonment that he considered “a purification, a punishment for the nation’s mistakes, for its lack of political intuition”.

Corneliu Coposu, in His Old Age

Florica Raica, a member of Corneliu Coposu’s party, describes the Senior in some situations in the crypto-communist period. (In fata… , p. 383) Here is a scene that took place on the 29th of January 1990. “I could see Corneliu Coposu on the entrance stairs, impassive, under the commotion of booing and objects thrown over the closed gates, with a BBC reporter standing next to him and who was shooting lively; he was watching the aggressors with the serenity that only the extreme experience of the years of imprisonment could have given to him, it is difficult to be impressed by something after you have experienced the worst.”

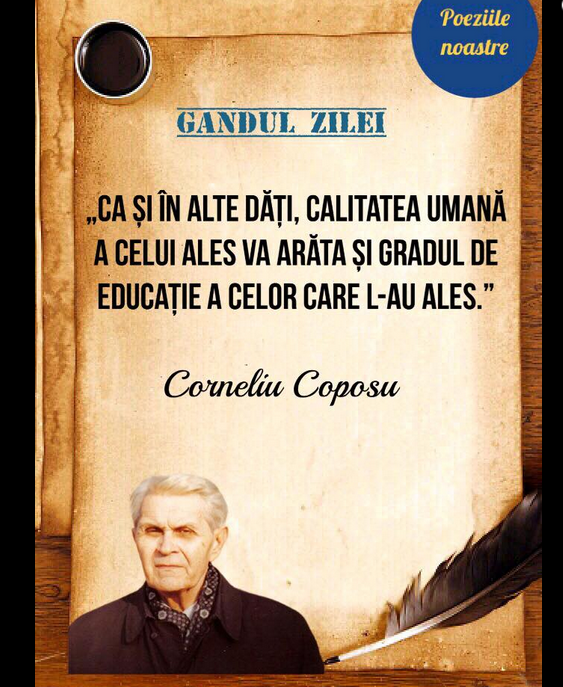

His portrait is captured by the voice of the street. “He would speak briefly and directly, clearly for everybody, and the answers to the reporters’ questions were often short syntheses which, in a few words, would catch the essential. On the political scene of those times, Corneliu Coposu was, undoubtedly, “a unique presence”.

“He was tall, handsome, with wonderful hair and eloquent hands. He was a great man, a perfect politician, of a European level, an example of morality” concludes the Christian – Democratic follower.

At his death, Gabriel Tepelea made him a bronze sketch. “Corneliu Coposu brought on the political scene in the post-revolutionary period a note of firmness and consistency. A man with the roots in the period of the interwar democracy, Corneliu Coposu would impress with the equilibrium of his conception, with the art of the negotiations. Loved by friends, respected by opponents, his disappearance will be dealt with heavily in the Romanian public life.”

A Portrait for Posterity – the Notes and the Reports of the Security

The most valuable gift for Posterity are the notes and reports made by the Security agents starting since April 1963 until December 1989.

On the 30th of April 1963, when Corneliu Coposu was a HD and was on house arrest at the Calmatui Valley, in the Baragan Plain, the Security opened an investigation into him. At 26 he would be followed at every step and the information would be systematized and processed.

Corneliu Coposu succeeded in prolonging an ideal for a century and a half, which is probably a unique performance in the history. The ideal of the Revolution that took place in 1848 was entirely transplanted into the Revolution in 1989. It is a challenge on behalf of the destiny and of a truly heavenly chance.

The ideas and ideals of a revolution were preserved and transferred through Corneliu Coposu to another generation, but as Ana Blandiana said, concerning the Coposu legacy, In fata, p. 389, “…the influence of great personalities does not act upon the first generation of descendants, but on the second one”. (In fata, op. cit., p. 389)

But during the almost two years of house arrest spent in Baragan, Corneliu Coposu was watched non-stop by the secret services, thus resulting a truthful and eloquent image offered, nolens volens, to the Posterity.

Here is the Senior’s Portrait, code name Cornel, Calinescu or Calin, as it appears in the Security informants’ conspirational notes. Agent Preda Viorel characterizes Coposu Cornel, in a note on the 9th of June 1963, shortly after he left the Ramnicu Sarat prison like “a real ghost”, Viata (approx. The Life), p. 91, as “an intelligent fellow, a communicative nature, a little too lazy and stubborn at times”. Describing the discussions with other people on house arrest, the informant considers that “All these discussions are listened to with interest because of the fact that COPOSU CORNEL makes in his narrations some jokes, ironies, which draw the others’ attention”. Agent Eugen Stanescu mentions in the same place that “COPOSU CORNEL enjoys high appreciation in the village, as he is a serious man, he is haughty enough, he has suffered a lot, he has had prestige even since he was in the penitentiary” (…) and as far as his political attitude is concerned “one could estimate that he follows the developing events with interest and tries to inspire the others with a lot of optimism.”

“His aspect is surprisingly good”, p. 93, shows a synthesis on the 15th of May 1964, based on the information provided by an informant from his entourage. He shows off to “best advantage”. He used to look like an obese young man. Nowadays he looks like a tall and thin young man, almost refined. He kept his hair and teeth. He is neatly dressed with his old clothes. He spent 15 years in various prisons and “got out on a stretcher”, he spent two years in Baragan and during the first year his mother accompanied him giving him all her care. One of his sisters, who is a chemist, was also able to help him regain his health”. Alt portet, ultimul (approx. Another Portrait, the Last One), pp. 100-101.

Chapter II The Life Philosophy

About Faith, Hope and Suicide

His vision on life and death bears the mark of Christian thinking. He admits with nonchalance that “I have never had any flaws in my faith. A strong, powerful faith in God and His justice”. But moreover, he seems to have despised the other values – atheism, duplicity, the lack of any nationalism. He was the son of a Greek – Catholic protopriest, fully kept his faith even when a question mark was put on the type of Christian – Democratic doctrine. “Whoever messes with the Greek – Catholic church will never win”, he said in a private conversation.

“Man without faith is not a complete man”, he motivates the option for a Christian – Democratic party in December ’89.

His role models were Saint Pavel, the apostle of Christian love, and especially Saint John the Baptist. In the interview published in the daily newspaper Viata Buzaului (approx. Life in Buzau) he confessed: “As far as love is concerned, which is our religion…the Christian religion is the religion based on love. This is how Pavel the Apostle defines it: Religion is love. Unfortunately, it is the less applied virtue.” Coposu considers that his butchers lacked precisely the feeling of Christian love, meaning the love for people. “The authority that governed us during those 50 years, not to mention the penitentiary authorities, was so faraway from the feeling of love for people, that they were almost alienated from the quality of being a human”. (ibidem)

“A saint that defeated the world through his death. John the Baptist, the symbol of character” is an article that he published in Romania Noua (approx. New Romania) when he was 22. Young Coposu develops a touching, vindictive thinking, with many eloges with references to contemporary characters, denoting an acute craving for social justice. “A providential man”, “the reforming genius of his contemporary society”, “born from the contrast of the sinful states as a protest of the divinity harmed by the flood of human turpitudes” (In fata istoriei, p. 425)

Despite an Asianic, and, here and there, Messianic oratory style, the article reaches prosaic conclusions, with direct references to the immediate present days, “he was, above all, an incorruptible, firm, unhesitating man, a man of character”. The savage prophet “preached the changing of the sick mentality which ruled the world by the means of the baptism of repentance. He fought against hypocrisy, urging his disciples to return from their sinful paths. Many have listened to him. Some of them followed him, others banished him. But St John went on, promptly, on the path of conscience, helped by the unbridled strength of his faith.”

The initiator reproved the despot himself, Herod the Emperor, and “not even when in chains did he deny his ethical convictions, but he happily paid with his life for the temerity with which he carried on his duty. Not even the butcher’s sword could turn away John the Baptist from the way of good and justice…” Priest’s Zaharia immortal son was a living example for the son of protopriest Valentin Coposu from the Salaj County. “The saint beheaded by Herodiade’s machinations remains the perfect embodiment of the man of character”, concludes young Coposu.

*

Faith proved its sacred and soul healing character in the communist prisons. “I witnessed many touching scenes that proved man’s love for man. For example, in conditions of extermination, I saw people who would give up half of their portion of food to save their extremely weakened fellows. It is something extraordinary in jail because the famine obsession turns people into animals. But I saw beautiful gestures, attempts to morally save the people. I saw gestures when priests, not all of them, but certain graced priests were trying to recover, by means of faith, some people that were sliding on the slope of desperation”. (interview, Viata Buzaului)

Hope – Faith – Salvation, a triad of the complete man who survives in inhuman conditions. But is the relation between faith and love biunivocal? “For the man who believes, the feeling of love is fundamental in the relations between people. The paradox is that suffering straightens him, it does not alienate him.” Therefore, suffering can be treated more like a proof of faith, following the Christian example, as the proof of proofs.

Even in the darkest periods he remained an optimist, he had the hope of the ultimate justice. In 1952, deported at the Channel, where he worked on a truck with Prince Serban Ghica, an informant wrote. “He sees the international situation very optimistically; that’s impossible, something must happen very soon.” (apud Tudor Calin Zarojanu, Viata lui Corneliu Coposu, Cu documente din arhiva fostei Securitati (approx. Corneliu Coposu’s Life, With Documents From the Archive of the Former Security) , second edition, Masina de Scris Publishing House, Bucharest, 2005, p. 67).

The suicidal thought as a final form of protest avoided him permanently, even if he witnessed many extreme gestures or suicidal attempts.

“The cons from the Pitesti penitentiary arrived at the Channel in 1950 with the intention of putting into practice the sordid experiment of brainwashing through continuous terror and self-exposure. Coposu was an indirect witness of a detainee’s suicide who refused to submit the tortures in the famous Hut 13. Doctor Simionescu’s case, a surgery professor and a famous surgeon, stirred Europe and ended the demented project. Tortured day and night by his re-educators, exhausted, doctor Simionescu decided to commit suicide in an exposing way. He deliberately entered the camp security area, wanted to force the barbed fence passage and was mortally shot. A suicidal gesture which will stand for the beginning of the end of the torturers from Pitesti.

Corneliu Coposu witnessed some extreme gestures in the prison Ramnicu Sarat too. After director’s Visinescu sadistic examinations, a teacher from Macrina village, Ramnicu Sarat county, committed suicide by hanging himself in the cell with the bed-sheet. Another case happened in the Ramnicu Sarat prison as well. In the autumn of 1959, Jenica Arnautu, a lieutenant discharged in 1946, an anticommunist partisan, sentenced to 25 years of hard labour, declared war to his torturers from the Ramnicu Sarat prison by refusing to eat. He was forcefully fed but died on hunger strike on the 2nd of November 1959 in cell number 4 nearby the cell where Corneliu Coposu was imprisoned.

Corneliu Coposu was the subject of all the correction methods, sole beating, crowbar beating, hanging with his head downwards, beatings with wet bed-sheets and with sand bags, the manege, where the detainee would run unclothed in a circle and would be whipped. “There is one torture system that I did not experience, he remembers, the one that I have heard of from the other detainees: the attempt of electrocution.”

Here is a confession, shocking indeed for a man who spent 17 years and a half in prison and was subject of these unimaginable ordeals. “I have never thought of committing suicide. I eliminated this idea from the beginning, at least as a thought. There were some who would think of committing suicide in difficult moments. Then…from the conversations with other people who were in the same situation…after useless expectations, some of them, I characterize them as insufficiently strengthened in their faith, would start to lose faith and wonder: there probably is not a God, if God is capable of allowing the horrors that we are going through to happen, it means that He does not exist”. (interview Viata Buzaului)

About Suffering, Patience and Hope

Saint Apostle Paul, in Romans 5:3, concentrated the essence of Christian thinking in a memorable phrase: “We praise our sufferings too, well-knowing that suffering brings patience, and patience brings endeavour, and endeavour brings hope”.

On his turn, Corneliu Coposu confesses that he learned many things from Iuliu Maniu, “especially the patience” which helped him to abide the 17 years and a half of imprisonment. “In prison, patience overpasses any imagination. I can tell you this because I tried it myself.” An idea expressed again in an interview given in Memoria magazine. “Prison is an exercise to train your patience. There, patience overpasses any imagination, I tried it myself.”

He learned many things from the example of the great ancestors, especially from Iuliu Maniu, the sphinx of Badacin, from whom he understood “patience above all”. The years of imprisonment passed “with patience and faith in God” and “for all of us, the survival in the communist holocaust required a lot of faith and ideals”, he confesses in an interview appeared in Romania Libera in March 1994.

Corneliu Coposu made many bets with history. “Be careful because many of my forecasts became true. Even if I had to wait for a generation to pass. In prison, patience overpasses any imagination. I can tell you this because I tried it myself. I was right when I said that communism would fall. I am also right when I tell you that we shall get rid of its last flaws. The past and present scandalmongers will also disappear. Don’t worry.”

Corneliu Coposu clearly said that for him everything was reduced to hope. “Undoubtedly, hope was the most useful for me. You said confidence, I say hope because I am a Latinist . Hope in the days to come, hope in the future of Romania, hope in the fall of communism. This essay can be ended with Saint Paul’s words too. “Look carefully how they ended their lives and follow their faith” (Hebrews 13:7)

“I had hope that I would get out of jail and that communism would fall”, says the Senior tersely in an interview given in 1994 to Radio Campus from Buzau.

“Hope has never left me in my whole life” he confesses in the same interview which he gave shortly after he had received the Legion of Honour.

Not even in the darkest years did he fall on “the slope of despair”. The Hope and the Intuition of the Romanian people, “accompanied by God’s finger who intervenes from time to time in the history of a miserable people justify me to think that we shall get rid of the misery, the catastrophe that the country faces and that we are heading towards the good.”

About Torturers, Forgiveness And the Expiation of the Sins

“There is neither sympathy, nor mercy for the people’s enemies” was the message on the frontispiece of the Pitesti prison.

“To be forgiven, like the robber on the cross!” Corneliu Coposu confesses a year before his death. (interview for Viata Buzaului)

“I have seen before people who slapped me, hanged me on an iron bar and insulted me in all ways. I want you to know that I would take the insult on me. I didn’t feel humiliated by the curses. I don’t spite or hate those who lowered themselves to the horrible crimes that the 50 years of communism recorded. I believe that the people who got to degrade themselves up to the point of torturing their fellows, without any kind of justification, lost the quality of humans and that it would be an honour for them to have feelings of enmity against them. To be forgiven, like the robber on the cross!”. The doctor in Law of the Law and State Sciences Faculty of Cluj knew very well the relations in the primary communities, coordinated by the principle an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. But he abhorred not only the feeling of hatred, but also the feeling of enmity. Was he carrying the Christian feeling of love for his fellows or maybe something deeper?

About Fortune, Poverty and Public Functions

The wise carries his fortune, says a Greek philosopher. For Corneliu Coposu there was no other virtue more profound than an austere life. A modest life, based on principles and on a permanent and total reconciliation with a conscience which was just as clean. This was the Coposian ideal. The phantasmagorias appeared after the Revolution but also at his arrest in 1947 did not affect him. In an interview which I had the honour to take him in 1991 I asked him about the truth dear to the anti-Coposu propaganda. I brought him a reportage from a newspaper, very serious on the other hand, which described his “adventures” in a village in Ardeal. The Senior was said to have been chased by the peasants while he was trying to get back his estates confiscated by the communist state. I asked him directly about the fortune that he had before the war and how he administrated it. My question, naïve through its simplicity, made him burst in laughter. “My ideological faith was my only fortune”, the Senior answered.

The documents from the archive of the former Security describe its torturers’ disorientation, their conscience issues when the problem of the goods owned by Iuliu Maniu’s nephew arose. There are repeated addresses, really desperate requests on behalf of some people educated in the Marxist spirit of class fight between the rich, the exploiters’ class and the poor, the exploited who had only the strength of their arms at their disposal.

His public accusers fell in the same trap, forced to convict him before judging him. They were disoriented, standing in front of a harmless class enemy, a truly poor one. In August 1955, the date of his proper trial, - until then he stayed in prison without a trial - , the president of the Military Tribunal requested “the proof for the fortune owned by the defendant Corneliu Coposu”. On the 7th of August 1955, his mother, Aurelia Coposu, sent a statutory declaration. “My son does not own any kind of movable or immovable property. The jewels, such as a watch and a ring, were sold by his wife to earn her living.” The register from the Jilava penitentiary is as conclusive as the declaration. At the PROPERTY section it was recorded, for both the past and the present, “W. Property”. Despite that, the judges gave him the harshest penalty, 15 years of hard labour and …the total confiscation of his fortune, the executors being supposed to apply the sentence.

Yet, the Security tried to fake a document concerning a small alcohol factory in a rural locality in the Alba County, but it was proven that his father Valentin Coposu had leased it for a very short period of time. His torturers gave the verdict with an unrelenting conscience; they were fighting an enemy who made part of the social class of the poor. They refused to accept the pure truth registered by the enemy of the working class. “I don’t own movable or immovable properties and I have never owned any either. (our emphasis) I was evicted from my last dwelling, Bucharest, Jianu Street, no. 72, which I had rented, in August 1947, after my arrest” and they requested for years the repetition of the addresses.

Only in 1957, after repeated summons, was the court forced to accept and register the obvious, admitting that “there is nothing that can be confiscated from Corneliu Coposu”. Meanwhile, the class enemy had already done 10 years of hard time!

***

“After all that has been said about my “fortune” it is natural for me to wait questions concerning my wealth or my departures abroad. All these aberrations couldn’t have come from the Security, because they knew what they had taken away from me and that I hadn’t left the country since 1938. But let them talk! Who is listening to them? I have always been and I am still very poor. We live as if we were under communism: we always ask only how much money there is in the house. But poverty never bothered us. (our emphasis) It’s the same thing if there is or there isn’t any money. I am my sisters’ fancyman. I know of nothing but my cigarettes. I have never bought anything for the house. (an excerpt from an interview given in March 1994, in Corneliu Coposu, In fata istoriei, p. 191)

A really painful truth about his welfare, on the terms that Coposu’s door was always open to all kinds of friends and an invitation to dinner was compulsory for Transylvanian hospitality.

The notes and reports of the Security partly register these truths. (see Tudor Calin Zarojanu, Viata lui Corneliu Coposu (approx. Corneliu Coposu’s Life), p. 139). In 1988 the source Petraru registers after a visit at Baia Mare “…Coposu is a harmless element as he is old. His only passion is smoking, he always has quality cigarettes with him.”

His despise for fortune was closely related to his refusal for functions and glory, for a social status which would have exempted him from worries, a thing which was possible exactly under communism. Under the regime, there are known bourgeois intellectuals who had a privileged status and an exceptional universitary career by making a simple compromise with the communist power. The brilliant professor of international law, Grigore Geamanu, the general secretary of the State Council in a confused period of the autochthonous communism is only one of the examples. Grigore Geamanu, Corneliu Coposu’s former subordinate in the party hierarchy before the war, made him such a proposal. The Security reports, but also the Senior’s memories, are eloquent.

In Fata, p. 85, “I was convoked the following day after the arrival – from Baragan, a.n. – at Gheorghe Gheorghiu – Dej who made me an apparently generous proposal of dissociation from the party and Maniu. He was offering me a very promising appointment as a State Contentious employer. I refused this proposal, of course, and consequently I looked for a job by myself through the Jobcenter. I finally got hired as a worker in the construction industry where I was promoted technical office worker on a minor position which I occupied until I turned the retirement age.” (In fata istoriei, op. cit., p. 85) Therefore, he refused a good, well-paid job which offered him a high social status in favour of the position of …an unskilled worker. At the same time, a universitary career was perfectly credible and probable, he had been awarded a doctor’s degree in juridical sciences and had taught at the Penal Law Department of the University of Cluj. All the great professors of the Law Faculties of Bucharest and Cluj in the 70’s had a political past which was even more colourful than the Senior’s. With awful qualms, the communist leader Gheorghiu – Dej released when on their death beds 10 personalities imprisoned in the Ramnicu Sarat penitentiary, and the communist leader Ion Gheorghe Maurer was known for the effort of recovering some interwar personalities.

Corneliu Coposu could have taken this step, we are in the possession of the confession that Grigore Geamanu made him these proposals, when he was a secretary of the State Council, a function of great respect at that time. He preferred work to shovel and to live in misery than to accept the compromise of treason.

“At the Channel I re-qualified. I am a bricklayer and a house painter” (…) “When in need, I am ready to do one of these jobs. Anyway, I don’t want to be a lawyer or an industrial unit jurist anymore, I don’t want to be an office worker either…”, appears in a Security note in 1964. (Viata, p. 94). A year later, in 1965, when he returned to Bucharest, professor Grigore Geamanu calls Gheorghe Gheorghiu – Dej, (ibidem, p. 96) who thus excuses himself for the political prisons: There was nothing we could do because the Russians commanded us all the time. In order to compensate, he proposes him to become a solicitor for the State Council with a salary of 4.800 lei a month (an engineer would earn approximately 800 lei a month), provided that he signs a declaration. Dej also suggested him to rehabilitate him and Iuliu Maniu, to which he answered: Maniu would be more indicated to rehabilitate the communists. (Zarojanu, p. 96)

“My dear is dignified”, it is a declaration of his mother, Aurelia Coposu, Mommy, registered by an informer of the Security in 1965 a little time before Dej’s death. A simple employer of a construction site in the Capital, with his wife working for a registration service of the sick people in a hospital, Corneliu Coposu refused, despite his family’s precarious wealth, any offer of collaboration. “It is difficult, but my dear son won’t accept certain offers which were made to him in exchange for certain services, as he suffered too much in the past. My dear is dignified”, confesses the old lady who had accompanied her son on house arrest in Baragan.