Source: rri.ro

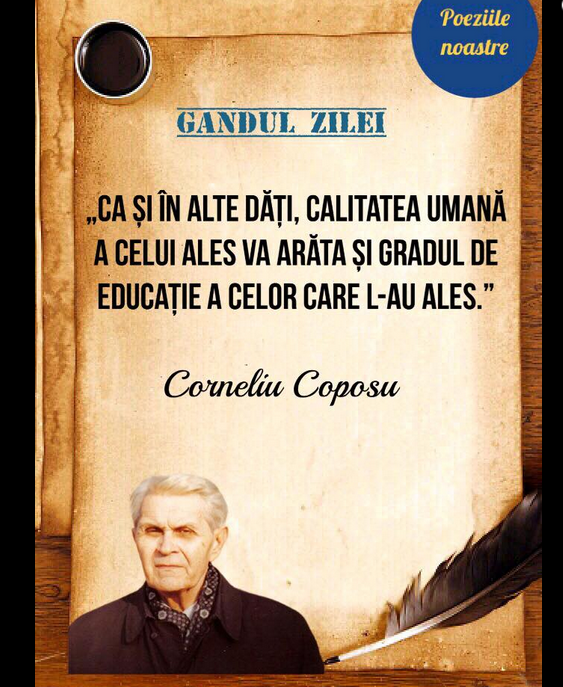

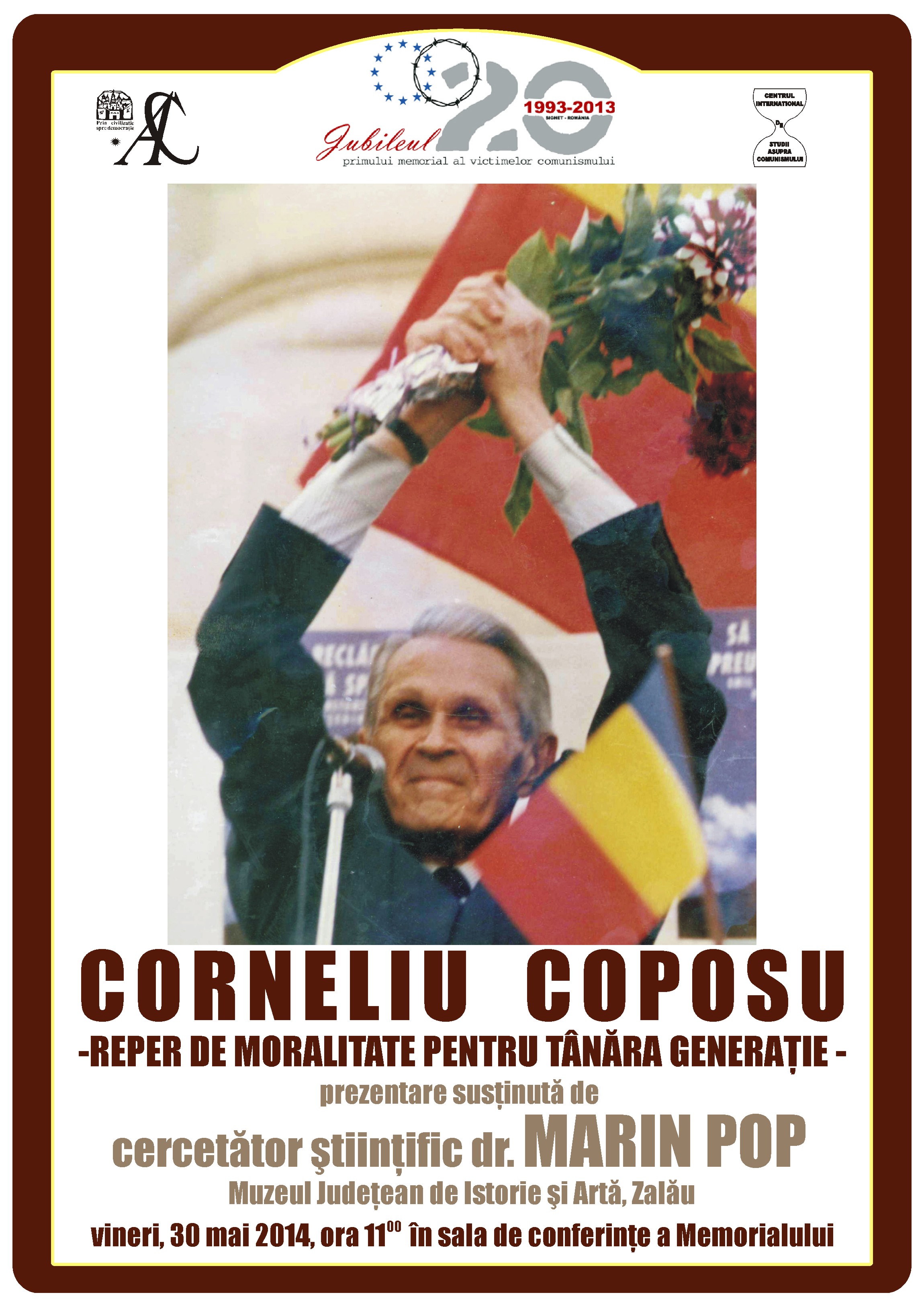

Corneliu Coposu was the quintessential Romanian politician, who kept in touch with democratic Romania before the communist dictatorship. He made an essential contribution to the rebirth of the democratic spirit of 1989. Romanian society owes him hugely for the role model he constituted, for his faith in the duty to fight for freedom, justice and honor, for the devotion he showed his comrades in the Romanian Gulag.

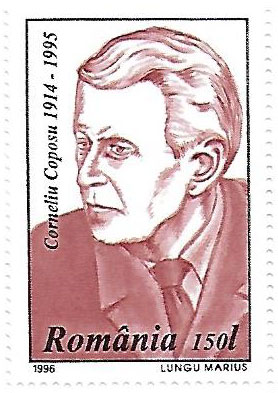

He was born on May 20, 1914, a Greek Catholic priest’s son, in north western Romania. He read law, and got his PhD at Cluj University. He was a personal assistant to National Peasant Party leader Iuliu Maniu. As such, he was arrested on July 14, 1947, alongside the entire leadership of the party, in a political frame-up of the communist government. He was sentenced to life in prison, and was released in the 1964 amnesty, after 17 years of hard time, 9 of which were spent in solitary at the Ramnicu Sarat prison. Corneliu Coposu survived the extermination regime imposed after 1945. Asked in 1993 by journalist Lucia Hossu-Longin whether he would have done things differently, he said no.

Corneliu Coposu: “No. I took stock of my past, looked back through all the suffering and misery I had to put up with in jail, in all the years of detention, during the persecutions after I was released, and I don’t think I actually had a choice. I would go through the same in the blink of an eye. I believe our destinies are given to us. I am not a fatalist, but I believe that if I was presented with alternatives, I would choose the same past I lived with serenity.”

Meeting such people is a privilege. For Corneliu Coposu, the cornerstone of his life was the time he spent in Ramnicu Sarat prison:

Corneliu Coposu: “The Ramnicu Sarat prison had 34 cells, 16 each on the ground floor and first floor, divided by a wire fence. There were two side cells and 4 solitary cells in the basement. Each cell was 3 by 2 meters. They were laid out in a honeycomb, 3 meters high there was an inaccessible little window, 45 by 30 cm wide, shuttered on the outside, not letting light in. There was a 15 watt light bulb shining at all times, which shed a light as if in a funeral home. There was no heating, the jail was built sometime around 1900, with thick walls. It had two rows of very high walls, 5 to 6 meters high, with a running space between them. On the second wall there were the towers where armed soldiers stood guard.”

The totalitarian regime did not treat people as living beings, but rather as numbers. In 1993, Corneliu Coposu reminisced about his life in prison:

Corneliu Coposu: ‘Each prisoner had a number which was the number of their cell, no one had a name. We were identified by the cell we were in. Each inmate was banned from speaking to others and having any ties with others, and most conversations were through Morse code knocked into the walls, until that was uncovered as well, and severe punishment was meted out. After that we coughed out Morse code to each other, which was exhausting, especially given how emaciated we were. I had cell number 1, and in cell 32, above me, was Ion Mihalache, who could be got in touch with by Morse code for 4 or 5 years, until he lost his hearing so much he would not react even to the knocks on the walls.”

After 1989, Corneliu Coposu believed Romania needed a strong personality to rebuild the country and restore its confidence. He believed that person was King Mihai I.

Corneliu Coposu: “My royalist attitude is based on my firm conviction that right now in Romania there is no one who has the vocation of polarizing the sympathies and confidence of the majority of the population aside from King Mihai. There is no one else. Since there is no such person in our political environment, to enjoy the confidence of the majority population, to guarantee domestic stability and trust abroad, our only recourse is the king who put fatherland first in 1944, with a staunch anti-communist attitude, who showed the prestige and wisdom of being an impartial arbiter in Romanian politics. The motivation of this royalist attitude is pragmatic, leaving aside any sentimentalism and romanticism. If there was any other personality able to gain the trust and the sympathy of the Romanian people, maybe a restoration of monarchy would not be necessary. We cannot create first rank personalities as if growing chicken in a factory. We would need 30 to 40 more years were we to follow such an objective.”

In 2014, the whole of Europe observed the centennial of WWI. Romania also celebrated 100 years since the birth of Corneliu Coposu, the man that helped the country find the right path.